Though I’m a qual, I started quantifying my self a year ago.

Not Even Started Yet

This post is long. You’ve been warned.

This post is about my experience with the Quantified Self (QuantSelf). As such, it may sound quite enthusiastic, as my perspective on my own selfquantification is optimistic. I do have several issues with the Quantified Self notion generally and with the technology associated with selfquantification. Those issues will have to wait until a future blogpost.

While I realize QuantSelf is broader than fitness/wellness/health tracking, my own selfquantification experience focuses on working with my body to improve my health. My future posts on the Quantified Self would probably address the rest more specifically.

You might notice that I frequently link to the DC Rainmaker site, which is a remarkably invaluable source of information and insight about a number of things related to fitness and fitness technology. Honestly, I don’t know how this guy does it. He’s a one-man shop for everything related to sports and fitness gadgets.

Though many QuantSelf devices are already available on the market, very few of them are available in Quebec. On occasion, I think about getting one shipped to someone I know in the US and then manage to pick it up in person, get a friend to bring it to Montreal, or get it reshipped. If there were such a thing as the ideal QuantSelf device, for me, I might do so.

(The title of this post refers to the song Body and Soul, and I perceive something of a broader shift in the mind/body dualism, even leading to post- and transhumanism. But this post is more about my own self.)

Quaint Quant

I can be quite skeptical of quantitative data. Not that quants aren’t adept at telling us very convincing things. But numbers tend to hide many issues, when used improperly. People who are well-versed in quantitative analysis can do fascinating things, leading to genuine insight. But many other people use numbers as a way to “prove” diverse things, sometimes remaining oblivious to methodological and epistemological issues with quantification.

Still, I have been accumulating fairly large amounts of quantitative data about my self. Especially about somatic dimensions of my self.

Started with this a while ago, but it’s really in January 2013 that my Quantified Self ways took prominence in my life.

Start Counting

It all started with the Wahoo Fitness fisica key and soft heartrate strap. Bought those years ago (April 2011), after thinking about it for months (December 2010).

Had tried different exercise/workout/fitness regimens over the years, but kept getting worried about possible negative effects. For instance, some of the exercises I’d try in a gym would quickly send my heart racing to the top of my healthy range. Though, in the past, I had been in a more decent shape than people might have surmised, I was in bad enough shape at that point that it was better for me to exercise caution while exercising.

At least, that’s the summary of what happened which might make sense to a number of people. Though I was severely overweight for most of my life, I had long periods of time during which I was able to run up long flights of stairs without getting out of breath. This has changed in the past several years, along with other health issues. The other health issues are much more draining and they may not be related to weight, but weight is the part on which people tend to focus, because it’s so visible. For instance, doctors who meet me for a few minutes, only once, will spend more time talking about weight than a legitimate health concern I have. It’s easy for me to lose weight, but I wanted to do it in the best possible way. Cavalier attitudes are discouraging.

Habits, Old and New

Something I like about my (in this case not-so-sorry) self is that I can effortlessly train myself into new habits. I’m exactly the opposite of someone who’d get hooked on almost anything. I never smoked or took drugs, so I’ve never had to kick one of those trickiest of habits. But I often stop drinking coffee or alcohol with no issue whatsoever. Case in point: I’m fairly well-known as a coffee geek yet I drank less than two full cups of coffee during the last two months.

Getting new habits is as easy for me as kicking new ones. Not that it’s perfect, of course. I occasionally forget to bring down the lid on the toilet seat. But if I put my mind to something, I can usually undertake it. Willpower, intrinsic motivation, and selfdiscipline are among my strengths.

My health is a significant part of this. What I started a year ago is an exercise and fitness habit that I’ve been able to maintain and might keep up for a while, if I decide to do so.

Part of it is a Pilates-infused yoga habit that I brought to my life last January and which became a daily routine in February or March. As is the case with other things in my life, I was able to add this routine to my life after getting encouragement from experts. In this case, yoga and Pilates instructors. Though it may be less impressive than other things I’ve done, this routine has clearly had a tremendous impact on my life.

Spoiler alert: I also took on a workout schedule with an exercise bike. Biked 2015 miles between January 16, 2013 and January 15, 2014.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

So Close, Yet So Far

Flashback to March, 2011. Long before I really got into QuantSelf.

At the time, I had the motivation to get back into shape, but I had to find a way to do it safely. The fact that I didn’t have access to a family physician played a part in that.

So I got the Wahoo key, a dongle which allows an iOS device to connect to ANT+ equipment, such as heartrate straps (including the one I bought at the same time as the key). Which means that I was able to track my heartrate during exercise using my iPod touch and iPad (I later got an iPhone).

Used that setup on occasion. Including at the gym. Worked fairly well as a way to keep track of my workouts, but I had some difficulty fitting gym workouts in my schedule. Not only does it take a lot of time to go to a gym (even one connected to my office by a tunnel), but my other health issues made it very difficult to do any kind of exercise for several hours after any meal. In fact, those other health issues made most exercise very unpleasant. I understand the notion of pushing your limits, getting out of your comfort zone. I’m fine with some types of discomfort and I don’t feel the need to prove to anyone that I can push my limits. But the kind of discomfort I’m talking about was more discouraging than anything else. For one thing, I wasn’t feeling anything pleasant at any point during or after exercising.

So, although I had some equipment to keep track of my workouts, I wasn’t working out on that regular a basis.

I know, typical, right? But that’s before I really started in QuantSelf.

Baby Steps

In the meantime (November, 2011), I got a Jawbone UP wristband. First generation.

That device was my first real foray into “Quantified Self”, as it’s normally understood. It allowed me to track my steps and my sleep. Something about this felt good. Turns out that, under normal circumstances, my stepcount can be fairly decent, which is in itself encouraging. And connecting to this type of data had the effect of helping me notice some correlations between my activity and my energy levels. There have been times when I’ve felt like I hadn’t walked much and then noticed that I had been fairly active. And vice-versa. I wasn’t getting into such data that intensely, but I had started accumulating some data on my steps.

Gotta start somewhere.

Sleepwalking

My sleep was more interesting, as I was noticing some difficult nights. An encouraging thing, to me, is that it usually doesn’t take me much time to get to sleep (about 10 minutes, according to the UP). Neat stuff, but not earth-shattering.

Obviously, the UP stopped working. Got refunded, and all, but it was still “a bummer”. My experience with the first generation UP had given me a taste of QuantSelf, but the whole thing was inconclusive.

Feeling Pressure

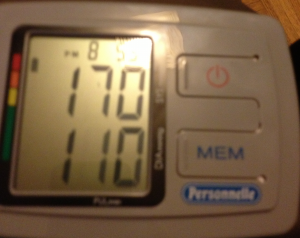

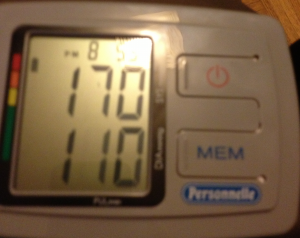

Fastforward to late December, 2012 and early January, 2013. The holiday break was a very difficult time for me, physically. I was getting all sorts of issues, compounding one another. One of them was a series of intense headaches. I had been getting those on occasion since Summer, 2011. By late 2012, my headaches were becoming more frequent and longer-lasting. On occasion, physicians at walk-in clinics had told me that my headaches probably had to do with blood pressure and they had encouraged me to take my pressure at the pharmacy, once in a while. While my pressure had been normal-to-optimal (110/80) for a large part of my life, it was becoming clear that my blood pressure had increased and was occasionally getting into more dangerous territory. So I eventually decided to buy a bloodpressure monitor.

Which became my first selfquantification method. Since my bloodpressure monitor is a basic no-frills model, it doesn’t sync to anything or send data anywhere. But I started manually tracking my bloodpressure by taking pictures and putting the data in a spreadsheet. Because the monitor often gives me different readings (especially depending on which arm I got them from), I would input lowest and highest readings from each arm in my spreadsheet.

My first bloodpressure reading, that first evening (January 3, 2013), was enough of a concern that a nurse at Quebec’s phone health consultation service recommended that I consult with a physician at yet another walk-in clinic. (Can you tell not having a family physician was an issue? I eventually got one, but that’s another post.) Not that it was an emergency, but it was a good idea to take this seriously.

So, on January 4, 2013, I went to meet Dr. Anthony Rizzuto, a general practitioner at a walk-in clinic in my neighbourhood.

Getting Attention

At the clinic, I was diagnosed with hypertension (high bloodpressure). Though that health issue was less troublesome to me than the rest, it got me the attention of that physician who gave me exactly the right kind of support. Thanks to that doctor, a bit of medication, and all sorts of efforts on my part, that issue was soon under control and I’m clearly out of the woods on this one. I’ve documented the whole thing in my previous blogpost. Summary version of that post (it’s in French, after all): more than extrinsic motivation, the right kind of encouragement can make all the difference in the world. (In all honesty, I already had all the intrinsic motivation I needed. No worries there!)

Really, that bloodpressure issue wasn’t that big of a deal. Sure, it got me a bit worried, especially about risks of getting a stroke. But I had been more worried and discouraged by other health issues, so that bloodpressure issue wasn’t the main thing. The fact that hypertension got me medical attention is the best part, though. Some things I was unable to do on my own. I needed encouragement, of course, but I also needed professional advice. More specifically, I felt that I needed a green light. A license to exercise.

Y’know how, in the US especially, “they” keep saying that you should “consult a physician” before doing strenuous exercise? Y’know, the fine print on exercise programs, fitness tools, and the like? Though I don’t live in the US anymore and we don’t have the same litigation culture here, I took that admonition to heart. So I was hesitant to take on a full fitness/training/exercise routine before I could consult with a physician. I didn’t have a family doctor, so it was difficult.

But, a year ago, I got the medical attention I needed. Since we’re not in the US, questions about the possibility to undertake exercise are met with some surprise. Still, I was able to get “approval” on doing more exercise. In fact, exercise was part of a solution to the hypertension issue which had brought this (minimal level of) medical attention to my case.

So I got exactly what I needed. A nod from a licensed medical practitioner. “Go ahead.”

Weight, Weight! Don’t Tell Me!

Something I got soon after visiting the clinic was a scale. More specifically, I got a Conair WW54C Weight Watchers Body Analysis Digital Precision Scale. I would weigh myself everyday (more than once a day, in fact) and write down the measures for total weight, body water percentage, and body fat percentage. As with the bloodpressure monitor, I was doing this by hand, since my scale wasn’t connected in any way to another device or to a network.

Weighing My Options

I eventually bought a second scale, a Starfrit iFit. That one is even more basic than the Weight Watchers scale, as it doesn’t do any “body analysis” beyond weight. But having two scales makes me much more confident about the readings I get. For reasons I don’t fully understand, I keep getting significant discrepancies in my readings. On a given scale, I would weigh myself three times and keep the average. The delta between the highest and lowest readings on that same scale would often be 200g or half a pound. The delta between the two scales can be as much as 500g or over one pound. Unfortunately, these discrepancies aren’t regular: it’s not that one scale is offset from the other by a certain amount. One day, the Weight Watchers has the highest readings and the Starfrit has the highest readings. I try to position myself the same way on each scale every time and I think both of them are on as flat a surface as I can get. But I keep getting different readings. I was writing down averages from both scales in my spreadsheet. As I often weighed myself more than once a day and would get a total of six readings every time, that was a significant amount of time spent on getting the most basic of data.

Food for Thought

At the same time, I started tracking my calories intake. I had done so in the past, including with the USDA National Nutrient Database on PalmOS devices (along with the Eat Watch app from the Hacker’s Diet). Things have improved quite a bit since that time. Not that tracking calories has become effortless, far from it. It’s still a chore, an ordeal, a pain in the neck, and possibly a relatively bad idea. Still, it’s now easier to input food items in a database which provides extensive nutritional data on most items. Because these databases are partly crowdsourced, it’s possible to add values for items which are specific to Canada, for instance. It’s also become easier to get nutritional values for diverse items online, including meals at restaurant chains. Though I don’t tend to eat at chain restaurants, tracking my calories encouraged me to do so, however insidiously.

But I digress.

Nutritional data also became part of my QuantSelf spreadsheet. Along with data from my bloodpressure monitor and body composition scale, I would copy nutritional values (protein, fat, sodium, carbohydrates…) from a database. At one point, I even started calculating my estimated and actual weightloss in that spreadsheet. Before doing so, I needed to know my calories expenditure.

Zipping

One of the first things I got besides the bloodpressure monitor and scale(s) was a fitbit Zip. Two months earlier (November, 2012), I had bought a fitbit One. But I lost it. The Zip was less expensive and, though it lacks some of the One’s features (tracking elevation, for instance), it was good enough for my needs at the time.

In fact, I prefer the Zip over the One, mostly because it uses a coin battery, so it doesn’t need to be recharged. I’ve been carrying it for a year and my fitbit profile has some useful data about my activity. Sure, it’s just a “glorified pedometer”. But the glorification is welcomed, as regular synchronization over Bluetooth is very useful a feature. My Zip isn’t a big deal, for me. It’s as much of a part of my life as my glasses, though I wear it more often (including during my sleep, though it doesn’t track sleep data).

Stepping UP

I also bought a new Jawbone UP. Yep, despite issues I had with the first generation one. Unfortunately, the UP isn’t really that much more reliable now than it was at the time. But they keep replacing it. A couple or weeks ago, my UP stopped working and I got a replacement. I think it’s the fifth one.

Despite its unreliability, I really like the UP for its sleeptracking and “gentle waking” features. If it hadn’t been for the UP, I probably wouldn’t have realized the importance of sleep as deeply as I have. In other words, the encouragement to sleep more is something I didn’t realize I needed. Plus, it’s really neat to wake up to a gentle buzz, at an appropriate point in my sleep cycle. I probably wouldn’t have gotten the UP just for this, but it’s something I miss every time my UP stops working. And there’s been several of those times.

My favourite among UP’s features is one they added, through firmware, after a while (though it might have been in the current UP from the start). It’s the ability to take “smart naps”. Meaning that I can set an alarm to wake me up after a certain time or after I’ve slept a certain amount of time. The way I set it up, I can take a 20 minute nap and I’ll be awaken by the UP after a maximum of 35 minutes. Without this alarm, I’d oversleep and likely feel more messed up after the nap than before. The alarm is also reassuring in that it makes the nap fit neatly my schedule. I don’t nap everyday, but naps are one of these underrated things I feel could be discussed more. Especially when it comes to heavy work sessions such as writing reports or grading papers. My life might shift radically in the near future and it’s quite possible that naps will be erased from my workweek indefinitely. But chances are that my workweek will also become much more manageable once I stop freelancing.

The UP also notifies me when I’ve been inactive for a certain duration (say, 45 minutes). It only does so a few times a month, on average, because I don’t tend to be that inactive. Exceptions are during long stretches of writing, so it’s a useful reminder to take a break. In fact, the UP just buzzed while I was writing this post so I should go and do my routine.

(It’s fun to write on my iPad while working out. Although, I tend to remain in the aerobic/endurance or even in the fitness/fatburning zone. I should still reach mile 2100 during this workout.)

Contrary to the fitbit Zip, the UP does require a charge on a regular basis. In fact, it seems that the battery is a large part of the reliability issue. So, after a while, I got into the habit of plugging my UP to the wall during my daily yoga/Pilates routine. My routine usually takes over half an hour and the UP is usually charged after 20 minutes.

Back UP

It may seem strange to have two activity trackers with complete feature overlap (there’s nothing the fitbit Zip does that the Jawbone UP doesn’t do). I probably wouldn’t have planned it this way, had I been able to get a Jawbone UP right at first. If I were to do it now, I might get a different device from either fitbit or Jawbone (the Nike+ FuelBand is offputting, to me).

I do find it useful to have two activity trackers. For one thing, the UP is unreliable enough that the Zip is useful as a backup. The Zip also stopped working once, so there’s been six periods of time during the past year during which I only had one fitness tracker. Having two trackers means that there’s no hiatus in my tracking, which has a significant impact in the routine aspect of selfquantification. Chances are slim that I would have completely given up on QuantSelf during such a hiatus. But I would probably have been less encouraged by selfquantification had I been forced to depend on one device.

Having two devices also helps me get a more accurate picture of my activities. Though the Zip and UP allegedly track the same steps, there’s usually some discrepancy between the two, as is fairly common among activity trackers. For some reasons, the discrepancy has actually decreased after a few months (and after I adapted my UP usage to my workout). But it’s useful to have two sources of data points.

Especially when I do an actual workout.

Been Working Out, Haven’t You?

In January, last year, I also bought an exercise bike, for use in my apartment. I know, sounds like a cliché, right? Getting an exercise bike after New Year? Well, it wasn’t a New Year’s resolution but, had it been one, I could be proud to say I kept it (my hypothetical resolution; I know, weird structure; you get what I mean, right?).

Right away, I started doing bike workouts on a very regular basis. From three to five times a week, during most weeks. Contrary to going to a gym, exercising at home is easy to fit in my freelancing schedule. I almost always work out before breakfast, so there’s no digestion issue involved. Since I’m by myself, it means I feel no pressure or judgment from others, a very significant factor in my case. Though I’m an extrovert’s extrovert (86 percentile), gyms are really offputting, to me. Because of my bodyshape, age, and overall appearance, I really feel like I don’t “fit”. It does depend on the gym, and I had a fairly good time at UMoncton’s Ceps back in 2003. But ConU’s gym wasn’t a place where I enjoyed working out.

My home workouts have become a fun part of my week. Not that the effort level is low, but I often do different things while working out, including listen to podcasts and music, reading, and even writing. As many people know, music can be very encouraging during a workout. So can a podcast, as it takes your attention elsewhere and you might accomplish more than you thought, during a podcast. Same thing with reading and writing, and I wrote part of this post while working out.

Sure, I could do most of this in a gym. The convenience factor at home is just too high, though. I can have as many things as I want by my sides, on a table and on a chair, so I just have to reach out when I need any of them. Apart from headphones, a music playing device, and a towel (all things I’d have at a gym) I typically have the following items with me when I do a home workout:

- Travel mug full of tea

- Stainless steel water bottle full of herbal tea (proper tea is theft)

- Britta bottle full of water (I do drink a lot of fluid while working out)

- three mobile devices (iPhone, iPad, Nexus 7)

- Small weights,

- Reading glasses

- Squeeze balls

Wouldn’t be so easy to bring all of that to a gym. Not to mention that I can wear whatever I want, listen to whatever I want, and make whatever noise I want (I occasionally yell beats to music, as it’s fun and encouraging). I know some athletic people prefer gym workouts over home ones. I’m not athletic. And I know what I prefer.

On Track

Since this post is nominally about QuantSelf, how do I track my workouts, you ask? Well, it turns out that my Zip and UP do help me track them out, though in different ways. To get the UP to track my bike workouts, I have to put it around one of my pedals, a trick which took me a while to figure out.

The Zip tracks my workouts from its usual position but it often counts way fewer “steps” than the UP does. So that’s one level of tracking. My workouts are part of my stepcounts for the days during which I do them.

Putting My Heart into IT

More importantly, though, my bike workouts have made my heartrate strap very useful. By pairing the strap with Digifit’s iBiker app, I get continuous heartrate monitoring, with full heartrate chart, notifications about “zones” (such as “fat burning”, “aerobic”, and “anaerobic”), and a recovery mode which lets me know how quickly my heartrate decreases after the workout. (I could also control the music app, but I tend to listen to Rdio instead.) The main reason I chose iBiker is that it works natively on the iPad. Early on, I decided I’d use my iPad to track my workouts because the battery lasts longer than on an iPhone or iPod touch, and the large display accommodates more information. The charts iBiker produces are quite neat and all the data can be synced to Digifit’s cloud service, which also syncs with my account on the fitbit cloud service (notice how everything has a cloud service?).

Heartrate monitoring is close to essential, for workouts. Sure, it’d be possible to do exercise without it. But the difference it makes is more significant than one might imagine. It’s one of those things that one may only grok after trying it. Since I’m able to monitor my heartrate in realtime, I’m able to pace myself, to manage my exertion. By looking at the chart in realtime, I can tell how long I’ve spent at which intensity level and can decide to remain in a “zone” for as long as I want. Continuous feedback means that I can experiment with adjustment to the workout’s effort level, by pedaling faster or increasing tension. It’s also encouraging to notice that I need increasing intensity levels to reach higher heartrates, since my physical condition has been improving tremendously over the past year. I really value any encouragement I can get.

Now, I know it’s possible to get continuous heartrate monitoring on gym equipment. But I’ve noticed in the past that this monitoring wasn’t that reliable as I would often lose the heartrate signal, probably because of perspiration. On equipment I’ve tried, it wasn’t possible to see a graphical representation of my heartrate through the whole workout so, although I knew my current heartrate, I couldn’t really tell how long I was maintaining it. Not to mention that it wasn’t possible to sync that data to anything. Even though some of that equipment can allegedly be used with a special key to transfer data to a computer, that key wasn’t available.

It’d also be possible to do continuous heartrate monitoring with a “fitness watch”. A big issue with most of these is that data cannot be transferred to another device. Several of the new “wearable devices” do add this functionality. But these devices are quite expensive and, as far as I can see in most in-depth reviews, not necessarily that reliable. Besides, their displays are so small that it’d be impossible to get as complete a heartrate chart as the one I get on iBiker. I got pretty excited about the Neptune Pine, though, and I feel sad I had to cancel my pledge at the very last minute (for financial reasons). Sounds like it can become a rather neat device.

As should be obvious, by now, the bike I got (Marcy Recumbent Mag Cycle ME–709 from Impex) is a no-frills one. It was among the least expensive exercise bikes I’ve seen but it was also one with high ratings on Amazon. It’s as basic as you can get and I’ve been looking into upgrading. But other exercise bikes aren’t that significantly improved over this one. I don’t currently have enough money to buy a highend bike, but money isn’t the only issue. What I’d really like to get is exercise equipment which can be paired with another device, especially a tablet. Have yet to see an exercise bike, rower, treadmill, or elliptical which does. At any price. Sure, I could eventually find ways to hack things together to get more communication between my devices, but that’d be a lot of work for little results. For instance, it might be possible to find a cadence sensor which works on an exercise bike (or tweak one to make it work), thereby giving some indication of pace/speed and distance. However, I doubt that there’s exercise equipment which would allow a tablet to control tension/strength/difficulty. It’d be so neat if it were available. Obviously, it’s far from a requirement. But none of the QuantSelf stuff is required to have a good time while exercising.

Off the Bike

I use iBiker and my heartrate monitor during other activities besides bike workouts. Despite its name, iBiker supports several activity types (including walking and hiking) and has a category for “Other” activities. I occasionally use iBiker on my iPhone when I go on a walk for fitness reasons. Brisk walks do seem to help me in my fitness regime, but I tend to focus on bike workouts instead. I already walk a fair bit and much of that walking is relatively intense, so I feel less of a need to do it as an exercise, these days. And I rarely have my heartrate strap with me when I decide to take a walk. At some point, I had bought a Garmin footpod and kept installing it on shoes I was wearing. I did use it on occasion, including during a trip to Europe (June–July, 2012). It tends to require a bit of time to successfully pair with a mobile app, but it works as advertised. Yet, I haven’t really been quantifying my walks in the same way, so it hasn’t been as useful as I had wished.

More frequently, I use iBiker and my heartrate strap during my yoga/Pilates routine. “Do you really get your heart running fast enough to make it worthwhile”, you ask? No, but that’s kind of the point. Apart from a few peaks, my heartrate charts during such a routine tends to remain in Zone 0, or “Warmup/Cooldown”. The peaks are interesting because they correspond to a few moves and poses which do feel a bit harder (such as pushups or even the plank pose). That, to me, is valuable information and I kind of wish I could see which moves and poses I’ve done for how long using some QuantSelf tool. I even thought about filming myself, but I would then need to label each pose or move by hand, something I’d be very unlikely to do more than once or twice. It sounds like the Atlas might be used in such a way, as it’s supposed to recognize different activities, including custom ones. Not only is it not available, yet, but it’s so targeted at the high performance fitness training niche that I don’t think it could work for me.

One thing I’ve noticed from my iBiker-tracked routine is that my resting heartrate has gone down very significantly. As with my recovery and the amount of effort necessary to increase my heartrate, I interpret this as a positive sign. With other indicators, I could get a fuller picture of my routine’s effectiveness. I mean, I feel its tremendous effectiveness in diverse ways, including sensations I’d have a hard time explaining (such as an “opening of the lungs” and a capacity to kill discomfort in three breaths). The increase in my flexibility is something I could almost measure. But I don’t really have tools to fully quantify my yoga routine. That might be a good thing.

Another situation in which I’ve worn my heartrate strap is… while sleeping. Again, the idea here is clearly not to measure how many calories I burn or to monitor how “strenuous” sleeping can be as an exercise. But it’s interesting to pair the sleep data from my UP with some data from my heart during sleep. Even there, the decrease in my heartrate is quite significant, which signals to me a large improvement in the quality of my sleep. Last summer (July, 2013), I tracked a night during which my average heartrate was actually within Zone 1. More recently (November, 2013), my sleeping heartrate was below my resting heartrate, as it should be.

Using the Wahoo key on those occasions can be quite inconvenient. When I was using it to track my brisk walks, I would frequently lose signal, as the dongle was disconnecting from my iPad or iPhone. For some reason, I would also lose signal while sleeping (though the dongle would remain unmoved).

So I eventually bought a Blue HR, from Wahoo, to replace the key+strap combination. Instead of ANT+, the Blue HR uses Bluetooth LE to connect directly with a phone or tablet, without any need for a dongle. I bought it in part because of the frequent disconnections with the Wahoo key. I rarely had those problems during bike exercises, but I thought having a more reliable signal might encourage me to track my activities. I also thought I might be able to pair the Blue HR with a version of iBiker running on my Nexus 7 (first generation). It doesn’t seem to work and I think the Nexus 7 doesn’t support Bluetooth LE. I was also able to hand down my ANT+ setup (Wahoo key, heartrate strap, and footpod) to someone who might find it useful as a way to track walks. We’ll see how that goes.

‘Figures!

Going back to my QuantSelf spreadsheet. iBiker, Zip, and UP all output counts of burnt calories. Since Digifit iBiker syncs with my fitbit account, I’ve been using the fitbit number.

Inputting that number in the spreadsheet meant that I was able to measure how many extra calories I had burnt as compared to calories I had ingested. That number then allowed me to evaluate how much weight I had lost on a given day. For a while, my average was around 135g, but I had stretches of quicker weightloss (to the point that I was almost scolded by a doctor after losing too much weight in too little time). Something which struck me is that, despite the imprecision of so many things in that spreadsheet, the evaluated weightloss and actual loss of weight were remarkably similar. Not that there was perfect synchronization between the two, as it takes a bit of time to see the results of burning more calories. But I was able to predict my weight with surprising accuracy, and pinpoint patterns in some of the discrepancies. There was a kind of cycle by which the actual number would trail the predicted one, for a few days. My guess is that it had to do with something like water retention and I tried adjusting from the lowest figure (when I seem to be the least hydrated) and the highest one (when I seem to retain the most water in my body).

Obsessed, Much?

As is clear to almost anyone, this was getting rather obsessive. Which is the reason I’ve used the past tense with many of these statements. I basically don’t use my QuantSelf spreadsheet, anymore. One reason is that (in March, 2013) I was advised by a healthcare professional (a nutrition specialist) to stop counting my calories intake and focus on eating until I’m satiated while ramping up my exercise, a bit (in intensity, while decreasing frequency). It was probably good advice, but it did have a somewhat discouraging effect. I agree that the whole process had become excessive and that it wasn’t really sustainable. But what replaced it was, for a while, not that useful. It’s only in November, 2013 that a nutritionist/dietician was able to give me useful advice to complement what I had been given. My current approach is much better than any other approach I’ve used, in large part because it allows me to control some of my digestive issues.

So stopping the calories-focused monitoring was a great idea. I eventually stopped updating most columns in my spreadsheet.

What I kept writing down was the set of readings from my two “dumb” scales.

Scaling Up

Abandoning my spreadsheet didn’t imply that I had stopped selfquantifying.

In fact, I stepped up my QuantSelf a bit, about a month ago (December, 2013) by getting a Withings WS–50 Smart Body Analyzer. That WiFi-enabled scale is practically the prototype of QuantSelf and Internet of Things devices. More than I had imagined, it’s “just the thing I needed” in my selfquantified life.

The main advantage it has over my Weight Watchers scale is that it syncs data with my Withings cloud service account. That’s significant because the automated data collection saves me from my obsessive spreadsheet while letting me learn about my weightloss progression. Bingo!

Sure, I could do the same thing by hand, adding my scale readings to any of my other accounts. Not only would it be a chore to do so, but it’d encourage me to dig too deep in those figures. I learnt a lot during my obsessive phase, but I don’t need to go back to that mode. There are many approaches in between that excessive data collection and letting Withings do the work. I don’t even need to explore those intermediary approaches.

There are other things to like about the Withings scale. One is Position Control™, which does seem to increase the accuracy of the measurements. Its weight-tracking graphs (app and Web) are quite reassuring, as they show clear trends, between disparate datapoints.

This Withings scale also measures heartrate, something I find less useful given my usage of a continuous heartrate monitor. Finally, it has sensors for air temperature and CO2 levels, which are features I’d expect in a (pre-Google) Nest product.

Though it does measure body fat percentage, the Withings Smart Body Analyzer doesn’t measure water percentage or bone mass, contrary to my low-end Weight Watchers body composition scale. Funnily enough, it’s around the time I got the Withings that I finally started gaining enough muscle mass to be able to notice the shift on the Weight Watchers. Prior to that, including during my excessive phase, my body fat and body water percentages added up to a very stable number. I would occasionally notice fluctuations of ~0.1%, but no downward trend. I did notice trends in my overall condition when the body water percentage was a bit higher, but it never went very high. Since late November or early December, those percentages started changing for the first time. My body fat percentage decreased by almost 2%, my body water percentage increased by more than 1%, and the total of the two decreased by 0.6%. Since these percentages are now stable and I have other indicators going in the same direction, I think this improvement in fat vs. water is real and my muscle mass did start to increase a bit (contrary to what a friend said can happen with people our age). It may not sound like much but I’ll take whatever encouragement I get, especially in such a short amount of time.

The Ideal QuantSelf Device

On his The Talk Show podcast, Gruber has been dismissing the craze in QuantSelf and fitness devices, qualifying them as a solved problem. I know what he means, but I gather his experience differs from mine.

I feel we’re in the “Rio Volt era” of the QuantSelf story.

The Rio Volt was one of the first CD players which could read MP3 files. I got one, at the time, and it was a significant piece of my music listening experience. I started ripping many of my CDs and creating fairly large compilations that I could bring with me as I traveled. I had a carrying case for the Volt and about 12 CDs, which means that I could carry about 8GB of music (or about 140 hours at the 128kbps bitrate which was so common at the time). Quite a bit less than my whole CD collection (about 150GB), but a whole lot more than what I was used to. As I was traveling and moving frequently, at the time, the Volt helped me get into rather… excessive music listening habits. Maybe not excessive compared to a contemporary teenager in terms of time, but music listening had become quite important to me, at a time when I wasn’t playing music as frequently as before.

There have been many other music players before, during, and after the Rio Volt. The one which really changed things was probably… the Microsoft Zune? Nah, just kidding. The iRiver players were much cooler (I had an iRiver H–120 which I used as a really neat fieldrecording device). Some people might argue that things really took a turn when Apple released the iPod. Dunno about that, I’m no Apple fanboi.

Regardless of which MP3-playing device was most prominent, it’s probably clear to most people that music players have changed a lot since the days of the Creative Nomad and the Rio Volt. Some of these changes could possibly have been predicted, at the time. But I’m convinced that very few people understood the implications of those changes.

Current QuantSelf devices don’t appear very crude. And they’re certainly quite diverse. CES2014 was the site of a number of announcements, demos, and releases having to do with QuantSelf, fitness, Internet of Things, and wearable devices (unsurprisingly, DC Rainmaker has a useful two-part roundup). But despite my interest in some of these devices, I really don’t think we’ve reached the real breakthrough with those devices.

In terms of fitness/wellness/health devices, specifically, I sometimes daydream about features or featuresets. For instance, I really wish a given device would combine the key features of some existing devices, as in the case of body water measurements and the Withings Smart Body Analyzer. A “killer feature”, for me, would be strapless continuous 24/7 heartrate monitoring which could be standalone (keeping the data without transmitting it) yet able to sync data with other devices for display and analysis, and which would work at rest as well as during workouts, underwater as well as in dry contexts.

Some devices (including the Basis B1 and Mio Alpha) seem to come close to this, but they all have little flaws, imperfections, tradeoffs. At an engineering level, it should be an interesting problem so I fully expect that we’ll at least see an incremental evolution from the current state of the market. Some devices measure body temperature and perspiration. These can be useful indicators of activity level and might help one gain insight about other aspects of the physical self. I happen to perspire profusely, so I’d be interested in that kind of data. As is often the case, unexpected usage of such tools could prove very innovative.

How about a device which does some blood analysis, making it easier to gain data on nutrients or cholesterol levels? I often think about the risks of selfdiagnosis and selfmedication. Those issues, related to QuantSelf, will probably come in a future post.

I also daydream about something deeper, though more imprecise. More than a featureset or a “killer feature”, I’m thinking about the potential for QuantSelf as a whole. Yes, I also think about many tricky issues around selfquantification. But I perceive something interesting going on with some of these devices. Some affordances of Quantified Self technology. Including the connections this technology can have with other technologies and domains, including tablets and smartphones, patient-focused medicine, Internet of Things, prosumption, “wearable hubs”, crowdsourced research, 3D printing, postindustrialization, and technological appropriation. These are my issues, in the sense that they’re things about which I care and think. I don’t necessarily mean issues as problems or worries, but things which either give me pause or get me to discuss with others.

Much of this will come in later posts, I guess. Including a series of issues I have with self-quantification, expanded from some of the things I’ve alluded to, here.

Walkthrough

These lines are separated from many of the preceding ones (I don’t write linearly) by a relatively brisk walk from a café to my place. Even without any QuantSelf device, I have quite a bit of data about this walk. For instance, I know it took me 40 minutes because I checked the time before and after. According to Google Maps, it’s between 4,1km and 4,2km from that café to my place, depending on which path one might take (I took an alternative route, but it’s probably close to the Google Maps directions, in terms of distance). It’s also supposed to be a 50 minute walk, so I feel fairly good about my pace (encouraging!). I also know it’s –20°C, outside (–28°C with windchill, according to one source). I could probably get some data about elevation, which might be interesting (I’d say about half of that walk was going up).

With two of my QuantSelf devices (UP and Zip), I get even more data. For instance, I can tell how many steps I took (it looks like it’s close to 5k, but I could get a more precise figure). I also realize the intensity of this activity, as both devices show that I started at a moderate pace followed by an intense pace for most of the duration. These devices also include this walk in measuring calories burnt (2.1Mcal according to UP, 2.7Mcal according to Zip), distance walked (11.2km according to Zip, 12.3km according to UP), active minutes (117’ Zip, 149’ UP), and stepcount (16.4k UP, 15.7k Zip). Not too shabby, considering that it’s still early evening as I write these lines.

Since I didn’t have my heartrate monitor on me and didn’t specifically track this activity, there’s a fair bit of data I don’t have. For instance, I don’t know which part was most strenuous. And I don’t know how quickly I recovered. If I don’t note it down, it’s difficult to compare this activity to other activities. I might remember more or less which streets I took, but I’d need to map it myself. These are all things I could have gotten from a fitness app coupled with my heartrate monitor.

As is the case with cameras, the best QuantSelf device is the one you have with you.

I’m glad I have data about this walk. Chances are I would have taken public transit had it not been for my QuantSelf devices. There weren’t that many people walking across the Mont-Royal park, by this weather.

Would I get fitter more efficiently if I had the ideal tool for selfquantification? I doubt it.

Besides, I’m not in that much of a hurry.