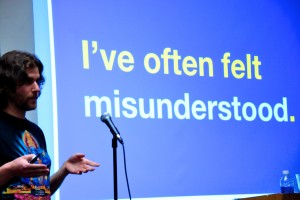

Academics are misunderstood.

Almost by definition.

Pretty much any academic eventually feels that s/he is misunderstood. Misunderstandings about some core notions in about any academic field are involved in some of the most common pet peeves among academics.

In other words, there’s nothing as transdisciplinary as misunderstanding.

It can happen in the close proximity of a given department (“colleagues in my department misunderstand my work”). It can happen through disciplinary boundaries (“people in that field have always misunderstood our field”). And, it can happen generally: “Nobody gets us.”

It’s not paranoia and it’s probably not self-victimization. But there almost seems to be a form of “onedownmanship” at stake with academics from different disciplines claiming that they’re more misunderstood than others. In fact, I personally get the feeling that ethnographers are more among the most misunderstood people around, but even short discussions with friends in other fields (including mathematics) have helped me get the idea that, basically, we’re all misunderstood at the same “level” but there are variations in the ways we’re misunderstood. For instance, anthropologists in general are mistaken for what they aren’t based on partial understanding by the general population.

An example from my own experience, related to my decision to call myself an “informal ethnographer.” When you tell people you’re an anthropologist, they form an image in their minds which is very likely to be inaccurate. But they do typically have an image in their minds. On the other hand, very few people have any idea about what “ethnography” means, so they’re less likely to form an opinion of what you do from prior knowledge. They may puzzle over the term and try to take a guess as to what “ethnographer” might mean but, in my experience, calling myself an “ethnographer” has been a more efficient way to be understood than calling myself an “anthropologist.”

This may all sound like nitpicking but, from the inside, it’s quite impactful. Linguists are frequently asked about the number of languages they speak. Mathematicians are taken to be number freaks. Psychologists are perceived through the filters of “pop psych.” There are many stereotypes associated with engineers. Etc.

These misunderstandings have an impact on anyone’s work. Not only can it be demoralizing and can it impact one’s sense of self-worth, but it can influence funding decisions as well as the use of research results. These misunderstandings can underminine learning across disciplines. In survey courses, basic misunderstandings can make things very difficult for everyone. At a rather basic level, academics fight misunderstandings more than they fight ignorance.

The main reason I’m discussing this is that I’ve been given several occasions to think about the interface between the Ivory Tower and the rest of the world. It’s been a major theme in my blogposts about intellectuals, especially the ones in French. Two years ago, for instance, I wrote a post in French about popularizers. A bit more recently, I’ve been blogging about specific instances of misunderstandings associated with popularizers, including Malcolm Gladwell’s approach to expertise. Last year, I did a podcast episode about ethnography and the Ivory Tower. And, just within the past few weeks, I’ve been reading a few things which all seem to me to connect with this same issue: common misunderstandings about academic work. The connections are my own, and may not be so obvious to anyone else. But they’re part of my motivations to blog about this important issue.

In no particular order:

- A thread on a mailing-list about linguistic anthropology. A paleoanthropologist interviewed for a radio show discussed language and cognitive evolution in a way which seemed to some linguistic anthropologists as conveying some misunderstandings about language.

- Two posts on anthro blog Savage Minds, one on Facebook’s founders Mark Zuckerberg’s (mis)understanding of potlatch and gift economies. The other on broad ideas about “gift economies” among what some have called technolibtertarians.

- A blogpost about “Common Knowledge” by writer, editor, and teacher Alexa Offenhauer.

- A “linktrail” about language diversity, about which I blogged for the Society for Linguistic Anthropology.

- A podcast episode about sociology which included a discussion of the relationships between sociologists and journalists.

- Several things on my favourite academic blog, Language Log, which demonstrate the distance between popular and academic ideas about language.

But, of course, I think about many other things. Including (again, in no particular order):

- A Language Log piece (that I consider seminal) about “raising standards by lowering them” (and extending the conversation between experts and the general population).

- A post by Montreal-based entrepreneur Austin Hill about the “social economy as a gift economy.”

- Two blogposts by LibriVox founder Hugh McGuire about “Why Academics Should Blog.” The first post made me react and the second post was in a small part motivated by my reaction. (As an aside, McGuire should be commended for his flexibility of thoughts. His abilirty to adapt his ideas as the result of thoughtful discussion has helped me have less “visceral” reactions.)

- Some comments about para-academic by McGill psychologist Dan Levitin in his popular book on music cognition.

- Bob White’s colloquium on intersubjectivity in ethnography (inspired by Johannes Fabian) which was part of a pivotal moment for me. (The connection to the issue at hand is in the importance of “being taken seriously.”)

- My work as a teacher of both upper-level and intro courses.

- Diverse conversations with fellow academics.

One discussion I remember, which seems to fit, included comments about Germaine Dieterlen by a friend who also did research in West Africa. Can’t remember the specifics but the gist of my friend’s comment was that “you get to respect work by the likes of Germaine Dieterlen once you start doing field research in the region.” In my academic background, appreciation of Germaine Dieterlen’s may not be unconditional, but it doesn’t necessarily rely on extensive work in the field. In other words, while some parts of Dieterlen’s work may be controversial and it’s extremely likely that she “got a lot of things wrong,” her work seems to be taken seriously by several French-speaking africanists I’ve met. And not only do I respect everyone but I would likely praise someone who was able to work in the field for so long. She’s not my heroine (I don’t really have heroes) or my role-model, but it wouldn’t have occurred to me that respect for her wasn’t widespread. If it had seemed that Dieterlen’s work had been misunderstood, my reflex would possibly have been to rehabilitate her.

In fact, there’s a strong academic tradition of rehabilitating deceased scholars. The first example which comes to mind is a series of articles (PDF, in French) and book chapters by UWO linguistic anthropologist Regna Darnell.about “Benjamin Lee Whorf as a key figure in linguistic anthropology.” Of course, saying that these texts by Darnell constitute a rehabilitation of Whorf reveals a type of evaluation of her work. But that evaluation comes from a third person, not from me. The likely reason for this case coming up to my mind is that the so-called “Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis” is among the most misunderstood notions from linguistic anthropology. Moreover, both Whorf and Sapir are frequently misunderstood, which can make matters difficulty for many linguistic anthropologists talking with people outside the discipline.

The opposite process is also common: the “slaughtering” of “sacred cows.” (First heard about sacred cows through an article by ethnomusicologist Marcia Herndon.) In some significant ways, any scholar (alive or not) can be the object of not only critiques and criticisms but a kind of off-handed dismissal. Though this often happens within an academic context, the effects are especially lasting outside of academia. In other words, any scholar’s name is likely to be “sullied,” at one point or another. Typically, there seems to be a correlation between the popularity of a scholar and the likelihood of her/his reputation being significantly tarnished at some point in time. While there may still be people who treat Darwin, Freud, Nietzsche, Socrates, Einstein, or Rousseau as near divinities, there are people who will avoid any discussion about anything they’ve done or said. One way to put it is that they’re all misunderstood. Another way to put it is that their main insights have seeped through “common knowledge” but that their individual reputations have decreased.

Perhaps the most difficult case to discuss is that of Marx (Karl, not Harpo). Textbooks in introductory sociology typically have him as a key figure in the discipline and it seems clear that his insight on social issues was fundamental in social sciences. But, outside of some key academic contexts, his name is associated with a large series of social events about which people tend to have rather negative reactions. Even more so than for Paul de Man or Martin Heidegger, Marx’s work is entangled in public opinion about his ideas. Haven’t checked for examples but I’m quite sure that Marx’s work is banned in a number of academic contexts. However, even some of Marx’s most ardent opponents are likely to agree with several aspects of Marx’s work and it’s sometimes funny how Marxian some anti-Marxists may be.

But I digress…

Typically, the “slaughtering of sacred cows” relates to disciplinary boundaries instead of social ones. At least, there’s a significant difference between your discipline’s own “sacred cows” and what you perceive another discipline’s “sacred cows” to be. Within a discipline, the process of dismissing a prior scholar’s work is almost œdipean (speaking of Freud). But dismissal of another discipline’s key figures is tantamount to a rejection of that other discipline. It’s one thing for a physicist to show that Newton was an alchemist. It’d be another thing entirely for a social scientist to deconstruct James Watson’s comments about race or for a theologian to argue with Darwin. Though discussions may have to do with individuals, the effects of the latter can widen gaps between scholarly disciplines.

And speaking of disciplinarity, there’s a whole set of issues having to do with discussions “outside of someone’s area of expertise.” On one side, comments made by academics about issues outside of their individual areas of expertise can be very tricky and can occasionally contribute to core misunderstandings. The fear of “talking through one’s hat” is quite significant, in no small part because a scholar’s prestige and esteem may greatly decrease as a result of some blatantly inaccurate statements (although some award-winning scholars seem not to be overly impacted by such issues).

On the other side, scholars who have to impart expert knowledge to people outside of their discipline often have to “water down” or “boil down” their ideas and, in effect, oversimplifying these issues and concepts. Partly because of status (prestige and esteem), lowering standards is also very tricky. In some ways, this second situation may be more interesting. And it seems unavoidable.

How can you prevent misunderstandings when people may not have the necessary background to understand what you’re saying?

This question may reveal a rather specific attitude: “it’s their fault if they don’t understand.” Such an attitude may even be widespread. Seems to me, it’s not rare to hear someone gloating about other people “getting it wrong,” with the suggestion that “we got it right.” As part of negotiations surrounding expert status, such an attitude could even be a pretty rational approach. If you’re trying to position yourself as an expert and don’t suffer from an “impostor syndrome,” you can easily get the impression that non-specialists have it all wrong and that only experts like you can get to the truth. Yes, I’m being somewhat sarcastic and caricatural, here. Academics aren’t frequently that dismissive of other people’s difficulties understanding what seem like simple concepts. But, in the gap between academics and the general population a special type of intellectual snobbery can sometimes be found.

Obviously, I have a lot more to say about misunderstood academics. For instance, I wanted to address specific issues related to each of the links above. I also had pet peeves about widespread use of concepts and issues like “communities” and “Eskimo words for snow” about which I sometimes need to vent. And I originally wanted this post to be about “cultural awareness,” which ends up being a core aspect of my work. I even had what I might consider a “neat” bit about public opinion. Not to mention my whole discussion of academic obfuscation (remind me about “we-ness and distinction”).

But this is probably long enough and the timing is right for me to do something else.

I’ll end with an unverified anecdote that I like. This anecdote speaks to snobbery toward academics.

[It’s one of those anecdotes which was mentioned in a course I took a long time ago. Even if it’s completely fallacious, it’s still inspiring, like a tale, cautionary or otherwise.]

As the story goes (at least, what I remember of it), some ethnographers had been doing fieldwork in an Australian cultural context and were focusing their research on a complex kinship system known in this context. Through collaboration with “key informants,” the ethnographers eventually succeeded in understanding some key aspects of this kinship system.

As should be expected, these kinship-focused ethnographers wrote accounts of this kinship system at the end of their field research and became known as specialists of this system.

After a while, the fieldworkers went back to the field and met with the same people who had described this kinship system during the initial field trip. Through these discussions with their “key informants,” the ethnographers end up hearing about a radically different kinship system from the one about which they had learnt, written, and taught.

The local informants then told the ethnographers: “We would have told you earlier about this but we didn’t think you were able to understand it.”