Did my inaugural cook in the 14.5″ Weber Smokey Mountain my lifepartner is giving me for my birthday (she knows I don’t like surprises).

Will probably post some written notes of my smoking endeavours, at some point. In the meantime, some pictures documenting the whole thing.

Category Archives: satisfaction

Santé encourageante

Il y a un an, jour pour jour, aujourd’hui, j’étais dans un piteux état, physiquement. Aujourd’hui, je suis dans la meilleure forme physique que j’ai été depuis au moins dix ans. Une chance que j’ai eu un peu d’encouragement.

J’hésite à écrire ce billet. Bloguer à propos de ma santé a pas toujours des effets très positifs. Mais je crois que c’est important, pour moi, de décrire tout ça. Pour moi-même, d’abord, parce que j’aime bien les anniversaires. Mais pour les autres, aussi, si ça peut les encourager. J’espère simplement que ça peut m’aider à parler moins de santé et de me concentrer sur autres choses. Avec une énergie renouvelée, je suis prêt à passer à d’autres étapes. Peu importe ce qui arrive, 2014 risque d’être une année très différente de 2013.

Depuis plusieurs années, ma condition physique a été une source de beaucoup de soucis et, surtout, de découragement. Il y a près de vingt ans, j’ai commencé à souffrir de divers problèmes de santé. Jusqu’à maintenant, j’ai aucune idée de ce qui s’est vraiment passé. Ma période la plus sombre a débuté par un ulcère d’estomac qui fut suivi de reflux gastro-œsophagien. Par la suite, j’ai subi des problèmes chroniques sur lesquels je n’élaborerai plus (l’ayant fait plus tôt), que j’ai trouvé particulièrement handicapants. Je commence à peine à me sortir de tout ça. Et ça dure depuis mon deuxième séjour au Mali, en 2002.

À plusieurs reprises au cours de ces années, j’ai pris la décision de prendre ma santé en main. Pas si facile. J’avais toute la motivation du monde mais, au final, assez peu de support.

Oh, pas que les gens aient été de mauvaise volonté. Mes amis et mes proches ont fait tout ce qui leur était possible, pour m’aider. Mais c’est pas facile, pour plusieurs raisons. Une d’entre elles est que je suis «difficile à aider», en ce sens que j’accepte rarement de l’aide. Mais le problème le plus épineux c’est que l’aide dont j’avais besoin était bien spécifique. Beaucoup de choses que les gens font, de façon tout-à-fait anodine, ont surtout un impact négatif sur moi. Pas de leur faute, mais une petite phrase lancée comme si de rien n’était peut me décourager assez profondément. Sans compter que ces gens ne sont pas spécialistes de mes problèmes et que j’avais besoin de spécialistes. Au moins, un médecin généraliste ou autre professionnel de la santé (agréé par notre système médical) qui puisse me comprendre et me prendre au sérieux. Ma condition avait pu s’améliorer grâce à diverses personnes mais ces personnes n’ont que peu de possibilité d’agir, dans notre système de santé. Mon médecin de famille ayant arrêté de pratiquer, il me manquait une personne habilitée à m’aider en prenant mon cas en main.

C’est beaucoup ce qui s’est passé, en 2013, pour moi. C’est en ayant accès à quelques spécialistes que j’ai pu améliorer ma santé. Et tout ça a commencé le 3 janvier, 2013.

Je revenais de passer quelque-chose chez mon frère, à Aylmer. Ces quelques jours ont été très pénibles, pour moi. Je souffrais d’énormes maux de têtes, qui avaient commencé à se multiplier au cours des mois précédents et mes problèmes d’œsophage étaient tels que je n’en arrivais plus à dormir. Mes autres problèmes me décourageaient encore plus. Vraiment, «rien n’allait plus».

Pourtant, j’avais déjà fait beaucoup d’efforts pour me sentir mieux, pendant des années. Des efforts qui ne portaient fruit que sporadiquement et qui ne se remarquaient pas vraiment de l’extérieur. Une recette pour le découragement. Ma santé semblait sans issue. Dans de telles situations, «les gens» ont l’habitude de parler de résignation, de pointer vers leurs propres bobos, de minimiser la souffrance de l’autre… Normales, comme réactions. Mais pas très utiles dans mon cas.

Les choses ont commencé à changer dans la soirée du 3 janvier. Sachant que mes maux de tête pouvaient avoir un lien à l’hypertension, me suis acheté un tensiomètre à la pharmacie.

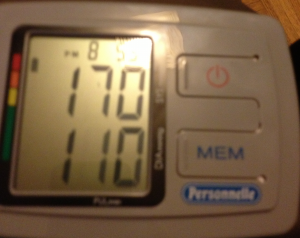

À 20:53, le 3 janvier 2013, j’ai fait une lecture de ma tension artérielle.

Systolique: 170 Diastolique: 110

Pas rassurant. Ni encourageant.

J’ai appelé la ligne Info-Santé, un service téléphonique inestimable mais sous-estimé qui est disponible au 811 partout au Québec. L’infirmière qui m’a répondu m’a encouragé, comme elles le font souvent, de consulter un médecin. Elle m’a aussi donné plusieurs conseils et donné de l’information au sujet des moments où ce serait réellement urgent de consulter dans les plus brefs délais. Pour certains, ça peut paraître peu. Mais, pour moi, ç’a été la première forme de support dont j’ai bénéficié pendant l’année. Le premier encouragement. Enfin, ma condition était suffisamment sérieuse pour que je sois pris au sérieux. Et de l’aide est disponible dans un tel cas.

C’est donc le lendemain, 4 janvier 2013, que je suis allé consulter. C’est un peu à ce moment que «ma chance a basculé». L’infirmière d’Info-Santé m’avait donné le numéro d’une clinique sans rendez-vous assez près de chez moi. Cette clinique offre un service d’inscription par téléphone, qui fait office de rendez-vous sans en être un. En appelant ce numéro tôt le matin, j’étais en mesure de me réserver une place pour voir un médecin dans une certaine plage horaire. J’ai donc pu consulter avec le Dr Anthony Rizzuto, en ce beau jour du 4 janvier 2013.

Le Dr Rizzuto avait l’attitude idéale pour me traiter. Sans montrer d’inquiétude, il a pris mon cas au sérieux. En m’auscultant et en me posant quelques questions, il a rapidement compris une grande partie de la situation et a demandé que je puisse passer un ECG à la clinique. Avec ces résultats et les autres données de mon dossier, il m’a offert deux options. Une était de traiter mon hypertension par l’alimentation. Perdre 10% de mon poids et de faire de l’exercice physique mais, surtout, éliminer tout sodium. L’autre option était de prendre un médicament, tout d’abord à très petite dose pour augmenter par la suite. Dans un cas comme dans l’autre, je pouvais maintenant être suivi. Les deux options étaient présentées sans jugement. Compte tenu de mes problèmes digestifs, la première me semblait particulièrement difficile, ce sur quoi le Dr Rizzuto a démontré la juste note d’empathie (contrairement à beaucoup de médecins et même un prof de psycho qui font de la perte de poids une question de «volonté»). Même si je suis pas friand des médicaments, j’ai opté pour la seconde option, tout en me disant que j’allais essayer la première. En deux-trois phrases, le Dr Rizzuto m’a donné plus d’encouragement que bien des gens.

J’ai pris mon premier comprimé de Ramipril en mangeant mon premier repas de la journée. Je réfléchissais à mon alimentation, à la possibilité d’éliminer le sodium et de réduire mon apport calorique, tout en faisant de l’exercice physique. Ayant essayé, à plusieurs reprises, de trouver une forme d’exercice qui me conviendrait et étant passé par des diètes très strictes, l’encouragement du Dr Rizzuto était indispensable.

Même si les gens confondent souvent les deux concepts, je considère l’encouragement comme étant bien plus important et bien plus efficace que la motivation. Faut dire que je suis de ceux qui sont mus par une très forte motivation intrinsèque. C’est d’ailleurs quelque-chose que je comprends de mieux en mieux, au fil des années. Malgré les apparences, je dispose d’une «volonté» (“willpower”) très forte. C’est un peu pour ça que je n’ai jamais été accro à quoi que ce soit (pas même le café) et c’est comme ça que j’arrive avec une certaine facilité à changer des choses, dans ma vie. Mais ma motivation nécessite quelque-chose d’autres. Du «répondant». De l’inspiration, dans des contextes de créativité. De l’encouragement, quand je suis désespéré.

Ma motivation intrinsèque d’atteindre un meilleur niveau de santé avait atteint son paroxysme des mois plus tôt et se maintient depuis tout ce temps. J’avais besoin de me sentir mieux. Même si je ne me souviens pas d’avoir manqué une seule journée de travail pendant ma vie adulte, mon niveau d’énergie avait considérablement baissé. Plus directement, les maux de tête que je subissais de plus en plus fréquemment me faisaient peur. J’ai dit, depuis, que c’est la peur de faire un AVC qui m’a poussé. C’est pas tout-à-fait exact. J’étais poussé par ma motivation intrinsèque, de toutes façons. L’éventualité de faire un AVC avait plutôt tendance à m’empêcher d’agir. Ce qui est vrai, c’est que c’est plus à l’AVC qu’à l’infarctus que je pensais, à cet époque. Certains peuvent trouver ça étrange, puisqu’un infarctus est probablement plus grave, surtout à mon âge. Mais la peur est pas nécessairement un phénomène rationnel et mes maux de tête me faisaient craindre un accident qui pourrait rendre ma vie misérable. D’où une «motivation» liée à l’AVC. J’ai pas vraiment l’habitude d’avoir peur. Mais cette éventualité me hantait bien plus que la notion d’avoir un autre trouble de santé, y compris le cancer. (Je connais plusieurs personnes qui ont eu le cancer et, même si certaines en sont décédées, je me sens mieux équipé pour affronter cette maladie que de survivre à un AVC.)

Donc, j’en suis là, mangeant un petit-déjeuner, dans un resto de mon quartier, réfléchissant à mes options. Et prenant la mesure des encouragements du Dr Rizzuto, pour utiliser l’approche diététique de l’hypertension (DASH). Il m’a pas dit que j’étais capable de le faire. Il m’a pas donné des trucs pour y arriver. Mais, surtout, il m’a pas jugé et il m’a pas balayé du revers de la main. En fait, il me prenait en main.

Sans devenir mon médecin de famille.

Ce n’est qu’en juin que, grâce au Dr Rizzuto, j’ai pu avoir un rendez-vous avec ma médecin de famille. Lors de ma première consultation avec le Dr Rizzuto, il me donné un petit signet sur lequel il y avait des informations au sujet du Guichet d’accès à un médecin de famille, dans mon quartier. J’ai appelé rapidement, mais le processus est long. D’ailleurs, le processus s’est étendu bien au-delà de ce qui était prévu, pour toutes sortes de raison. Même que la médecin de famille avec laquelle j’ai pu avoir un rendez-vous, la Dre Sophie Mourey, n’était pas la même personne qui m’était assignée. Reste que, sans l’approche encourageante du Dr Rizzuto, je n’aurais probablement pas de médecin de famille à l’heure qu’il est.

Et je n’aurais probablement pas accompli ce que j’ai pu accomplir dans l’année qui a suivi.

Qu’ai-je accompli? À la fois pas grand-chose et tout ce qui compte. J’ai fait plus de 2000km de marche à pieds et 1870 miles de vélo sur place (à une moyenne de 18miles/heure pendant environ trois heures par semaine, au cours des derniers mois). J’ai débuté une routine quotidienne de yoga (pour une moyenne de quatre heures par semaine, depuis l’été). J’ai baissé mon pouls au repos d’environ 90 battements par minute à moins de 60 battements par minute. J’ai évidemment baissé ma tension artérielle, d’abord aidé par le Ramipril (5mg), mais maintenant presque sous contrôle. Encore plus important pour moi, j’ai fini par trouver une façon de grandement diminuer certains de mes autres problèmes de santé, ce qui me donne l’espoir de pouvoir en enrayer certains au cours des prochains mois.

Donc, comme le disait la Dre Mourey, mon bilan de santé est bien encourageant.

Ah oui, incidemment… j’ai aussi perdu 15kg (33lbs.). Sans beaucoup d’effort et juste un petit peu de motivation.

Concierge-Style Service

Disclaimer: This is one of those blogposts in which I ramble quite a bit. I do have a core point, but I take winding roads around it. It’s also a post where I’m consciously naïve, this time talking about topics which may make economists react viscerally. My hope is that they can get past their initial reaction and think about “the fool’s truth”.

High-quality customer service is something which has a very positive effect, on me. More than being awed by it, I’m extremely appreciative for it when it’s directed towards me and glad it exists when other people take advantage of it.

And I understand (at least some of) the difficulties of customer service.

Never worked directly in customer service. I do interact with a number of people, when I work (teaching, doing field research, working in restaurants, or even doing surveys over the phone). And I’ve had to deal with my share of “difficult customers”, sometimes for months at a time. But nothing I’ve done was officially considered customer service. In fact, with some of my work, “customer service” is exactly the opposite of “what the job is about”, despite some apparent similarities.

So I can only talk about customer service as a customer.

As job sectors go, customer service is quite compatible with a post-industrial world. At the end of the Industrial Revolution, jobs in the primary and secondary sectors have decreased a lot in numbers, especially in the wealthiest parts of the World. The tertiary sector is rapidly growing, in these same contexts. We may eventually notice a significant move toward the quaternary sector, through the expansion of the “knowledge society” but, as far as I know, that sector employs a very small proportion of the active population in any current context.

Point is, the service sector is quite big.

It’s also quite diverse, in terms of activities as well as in terms of conditions. There are call centres where working conditions and salaries are somewhat comparable to factory work (though the latter is considered “blue collar” and the former “white collar”). And there are parts of the service industry which, from the outside, sound quite pleasant.

But, again, I’m taking the point of view of the customer, here. I really do care about working conditions and would be interested in finding ways to improve them, but this blogpost is about my reactions as someone on the other side of the relationship.

More specifically, I’m talking about cases where my satisfaction reaches a high level. I don’t like to complain about bad service (though I could share some examples). But I do like to underline quality service.

And there are plenty of examples of those. I often share them on Twitter and/or on Facebook. But I might as well talk about some of these, here. Especially since I’m wrapping my head about a more general principal.

A key case happened back in November, during the meetings of the American Anthropological Association, here in Montreal. Was meeting a friend of mine at the conference hotel. Did a Foursquare checkin there, while I was waiting, pointing out that I was a local. Received a Twitter reply from the hotel’s account, welcoming me to Montreal. Had a short exchange about this and was told that “if my friend needs anything…” Went to lunch with my friend.

Among the topics of our conversation was the presentation she was going to give, that afternoon. She was feeling rather nervous about it and asked me what could be done to keep her nervousness under control. Based on both personal experience and rumours, I told her to eat bananas, as they seem to help in relieving stress. But, obviously, bananas aren’t that easy to get, in a downtown area.

After leaving my friend, I thought about where to get bananas for her, as a surprise. Didn’t remember that there was a supermarket, not too far from the hotel, so I was at a loss. Eventually went back to the hotel, thinking I might ask the hotel staff about this. Turns out, it would have been possible to order bananas for my friend but the kitchen had just closed.

On a whim, I thought about contacting the person who had replied to me through the hotel’s Twitter account. Explained the situation, gave my friend’s room number and, within minutes, a fruit basket was delivered to her door. At no extra charge to me or to my friend. As if it were a completely normal thing to do, asking for bananas to be delivered to a room.

I’m actually not one to ask for favours, in general. And I did feel strange asking for these bananas. But I wanted to surprise my friend and was going to pay for the service anyway. And the “if she needs anything” message was almost a dare, to me. My asking for bananas was almost defiant. “Oh, yeah? Anything? How about you bring bananas to her room, then?” Again, I’m usually not like this but exchanges like those make me want to explore the limits of the interaction.

And the result was really positive. My friend was very grateful and I sincerely think it helped her relax before her presentation, beyond the effects of the bananas themselves. And it titillated my curiosity, as an informal observer of customer service.

Often heard about hotel concierges as the model of quality in customer service. This fruit basket gave me a taster.

What’s funny about «concierges» is that, as a Québécois, I mostly associate them with maintenance work. In school, for instance, the «concierge» was the janitor, the person in charge of cleaning up the mess left by students. Sounds like “custodian” (and “custodial services”) may be somewhat equivalent to this meaning of «concierge», among English-speaking Canadians, especially in universities. Cleaning services are the key aspect of this line of work. Of course, it’s important work and it should be respected. But it’s not typically glorified as a form of employment. In fact, it’s precisely the kind of work which is used as a threat to those whose school performance is considered insufficient. Condescending teachers and principals would tell someone that they could end up working as a «concierge» (“janitor”) if they didn’t get their act together. Despite being important, this work is considered low-status. And, typically, it has little to do with customer service, as their work is often done while others are absent.

Concierges in French apartment buildings are a different matter, as they also control access and seem to be involved in collecting rent. But, in the “popular imagination” (i.e., in French movies), they’re not associated with a very high quality of service. Can think of several concierges of this type, in French movies. Some of them may have a congenial personality. But I can’t think of one who was portrayed as a model of high-quality customer service.

(I have friends who were «concierges» in apartment buildings, here in Montreal. Their work, which they did while studying, was mostly about maintenance, including changing lightbulbs and shovelling snow. The equivalent of “building superintendent”, it seems. Again, important but devalued work.)

Hotel concierges are the ones English-speakers think of when they use the term. They are the ones who are associated with high-quality (and high-value) customer service. These are the ones I’m thinking about, here.

Hotel concierges’ “golden keys” («Clefs d’or») are as much of a status symbol as you can get one. No idea how much hotel concierges make and I’m unclear as to their training and hiring. But it’s clear that they occupy quite specific a position in the social ladder, much higher than that of school janitors or apartment concierges.

Again, I can just guess how difficult their work must be. Not only the activities themselves but the interactions with the public. Yet, what interests me now is their reputation for delivering outstanding service. The fruit basket delivered to my friend’s door was a key example, to me.

(I also heard more about staff in luxury hotels, in part from a friend who worked in a call centre for a hotel with an enviable reputation. The hospitality industry is also a central component of Swiss culture, and I heard a few things about Swiss hotel schools, including Lausanne’s well-known EHL. Not to mention contacts with ITHQ graduates. But my experience with this kind of service in a hotel context is very limited.)

And it reminds me of several other examples. One is my admiration for the work done by servers in a Fredericton restaurant. The food was quite good and the restaurant’s administration boasts their winelist. But the service is what gave me the most positive feeling. Those service were able to switch completely from treating other people like royalty to treating me like a friend. These people were so good at their job that I discussed it with some of them. Perhaps they were just being humble but they didn’t even seem to realize that they were doing an especially good job.

A similar case is at some of Siena’s best restaurants, during a stay with several friends. At most places we went, the service was remarkably impeccable. We were treated like we deserved an incredible amount of respect, even though we were wearing sandals, shorts, and t-shirts.

Of course, quality service happens outside of hotels and restaurants. Which is why I wanted to post this.

Yesterday, I went to the “Genius Bar” at the Apple Store near my university campus. Had been having some issues with my iPhone and normal troubleshooting didn’t help. In fact, I had been to the same place, a few months ago, and what they had tried hadn’t really solved the problem.

This time, the problem was fixed in a very simple way: they replaced my iPhone with a new one. The process was very straightforward and efficient. And, thanks to regular backups, setting up my replacement iPhone was relatively easy a process. (There were a few issues with it and it did take some time to do, but nothing compared to what it might have been like without cloud backups.)

Through this and previous experiences with the “Genius Bar“, I keep thinking that this service model should be applied to other spheres of work. Including healthcare. Not the specifics of how a “Genius Bar” works. But something about this quality of service, applied to patient care. I sincerely think it’d have a very positive impact on people’s health.

In a way, this might be what’s implied by “concierge medicine”: personalized healthcare services, centred on patients’ needs. But there’s a key difference between Apple’s “Genius Bar” and “concierge medicine”: access to the “Genius Bar” is open to all (customers of Apple products).

Sure, not everyone can afford Apple products. But, despite a prevailing impression, these products are usually not that much more expensive than those made by competitors. In fact, some products made by Apple are quite competitive in their market. So, while the concierge-style services offered by the “Genius Bar” are paid by Apple’s customers, costing those services as even the totality of the “Apple premium” might reveal quite decent a value proposition.

Besides, it’s not about Apple and it’s not really about costs. While Apple’s “Genius Bar” provided my inspiration for this post, I mostly think about quality of service, in general. And while it’s important for decision-makers to think about the costs involved, it’s also important to think about what we mean by high quality service.

One aspect of concierge-style service is that it’s adapted to specific needs. It’s highly customized and personalized, the exact opposite of a “cookie-cutter” approach. My experience at BrewBakers was like that: I was treated the way I wanted to be treated and other people were treated in a very different way. For instance, a server sat besides me as I was looking at the menu, as if I had been a friend “hanging out” with them, and then treated some other customers as if they were the most dignified people in the world. Can’t say for sure the other people appreciated it (looked like they did), but I know it gave me a very warm feeling.

Similar thing at the “Genius Bar”. I could hear other people being treated very formally, but every time I went I was treated with the exact level of informality that I really enjoy. Perhaps more importantly, people’s technology skills are clearly taken into account and they never, in my experience, represent a basis for condescension or for misguided advice. In other words, lack of knowledge of an issue is treated with an understanding attitude and a customer’s expertise on an issue is treated with the exact level of respect it deserves. As always, YMMV. But I’m consistently struck by how appropriately “Genius Bar” employees treat diverse degrees of technological sophistication. As a teacher, this is something about which I care deeply. And it’s really challenging.

While it’s flexible and adaptable, concierge-style service is also respectful, no matter what. This is where our experiences in Siena were so striking. We were treated with respect, even though we didn’t fit the “dress code” for any of these restaurants. And this is a city where, in our observations, people seemed to put a lot of care in what they wore. It’s quite likely that we were judged like annoying tourists, who failed to understand the importance of wearing a suit and tie when going to a “classy” restaurant. But we were still welcomed in these establishments, and nothing in the service made us perceive negatively judged by these servers.

I’ve also heard about hotel staff having to maintain their dignity while coping with people who broke much more than dress codes. And this applies whether or not these people are clients. Friends told me about how the staff at a luxury hotel may deal with people who are unlikely to be customers (including homeless people). According to these friends, the rule is to treat everyone with respect, regardless of which position in the social ladder people occupy. Having noticed a few occasions where respectful treatment was applied to people who are often marginalized, it gives me some of the same satisfaction as when I’m treated adequately.

In other words, concierge-style service is appropriate, “no matter what”. The payoff may not be immediately obvious to everyone, but it’s clearly there. For one thing, poor-quality service to someone else can be quite painful to watch and those of us who are empathetic are likely to “take our business elsewhere” when we see somebody else being treated with disrespect. Not to mention that a respectful attitude is often the best way to prevent all sorts of negative situations from happening. Plus, some high-status people may look like low-status ones in certain of these situations. (For instance, friend working for a luxury hotel once commented on some celebrities looking like homeless people when they appeared at the hotel’s entrance.)

Concierge-style service is also disconnected from business transactions. While the money used to pay for people providing concierge-style service comes from business transactions, this connection is invisible in the service itself. This is similar to something which seems to puzzle a number of people I know, when I mention it. And I’m having a hard time explaining it in a way that they understand. But it’s quite important in the case of customer service.

At one level, you may call it an illusion. Though people pay for a service, the service is provided as if this payment didn’t matter. Sure, the costs associated with my friend’s fruit basket were incurred in the cost of her room. But neither of us saw that cost. So, at that level, it’s as if people were oblivious to the business side of things. This might help explain it to some people, but it’s not the end of it.

Another part has to do with models in which the costs behind the service are supported by a larger group of people, for instance in the ad-based model behind newspapers and Google or in the shared costs model behind insurance systems (not to mention public sectors programs). The same applies to situation where a third-party is responsible for the costs, like parents paying for services provided to their children. In this case, the separation between services and business transactions is a separation between roles. The same person can be beneficiary or benefactor in the same system, but at different times. Part of the result is that the quality of the service is directed toward the beneficiary, even though this person may not be directly responsible for the costs incurred by this service. So, the quality of a service offered by Google has to do with users of that service, not with Google’s customers (advertisers). The same thing applies to any kind of sponsorship and can work quite well with concierge-level quality of service. The Apple Store model is a bit like this, in that Apple subsidizes its stores out of its “own pocket”, and seems to be making a lot of money thanks to them. It may be counterintuitive, as a model, and the distinction between paying for and getting a service may sound irrelevant. But, from the perspective of human beings getting this kind of service, the difference is quite important.

At another level, it’s a matter of politeness. While some people are fine talking financials about any kind of exchange, many others find open discussion of money quite impolite. The former group of people may find it absurd but some of us would rather not discuss the specifics of the business transactions while a service is given. And I don’t mean anything like the lack of transparency of a menu with no price, in a very expensive restaurant. Quite the contrary. I mean a situation where everybody knows how much things cost in this specific situation, but discussion of those costs happens outside of the service itself. Again, this may sound strange to some, but I’d argue that it’s a characteristic of concierge-style service. You know how much it costs to spend a night at this hotel (or to get a haircut from this salon). But, while a specific service is provided, these costs aren’t mentioned.

Another component of this separation between services and their costs is about “fluidity”. It can be quite inefficient for people to keep calculating how much a service costs, itemized. The well-known joke about an engineer asked to itemize services for accounting purposes relates to this. In an industrial context, every item can have a specific cost. Applying the same logic to the service sector can lead to an overwhelming overhead and can also be quite misleading, especially in the case of knowledge and creative work. (How much does an idea cost?) While concierge-style service may be measured, doing so can have a negative impact on the service itself.

Some of my thinking about services and their costs has to do with learning contexts. In fact, much of my thinking about quality of service has to do with learning, since teaching remains an important part of my life. The equation between the costs of education and the learning process is quite complex. While there may be strong correlations between socioeconomic factors and credentials, the correlation between learning and credential is seems to be weaker and the connection between learning and socioeconomic factors is quite indirect.

In fact, something which is counterintuitive to outsiders and misconstrued to administrators at learning institutions is the relationship between learning and the quality of the work done by a teacher. There are many factors involved, in the work of a teacher, from students’ prior knowledge to their engagement in the learning process, and from “time on task” to the compatibility between learning and teaching methods. It’s also remarkably difficult to measure teaching effectiveness, especially if one is to pay more than lipservice to lifelong learning. Also, the motivations behind a teacher’s work rarely have much to do with such things as differential pay. At the very least, it’s clear that dedicated teachers spend more time than is officially required, and that they do so without any expectation of getting more money. But they do expect (and often get) much more than money, including the satisfaction of a job well done.

The analogy between teaching and concierge services falls down quickly if we think that concierges’ customers are those who use their services. Even in “for-profit” schools, the student-teacher relationship has very little to do with a client-business relationship. Those who “consume” the learning process are learners’ future employers or society as a whole. But students themselves aren’t “consuming teaching”, they’re learning. Sure, students often pay a portion of the costs to run educational institutions (other costs being covered by research activities, sponsorships, government funding, alumni, and even parents). But the result of the learning process is quite different from paying for a service. At worst, students are perceived as the “products” of the process. At best, they help construct knowledge. And even if students are increasingly treated as if they were customers of learning institutions (including publicly-funded ones), their relationship to teachers is quite distinct from patronage.

And this is one place for a connection between teachers and concierges, having to do with the separation between services and their fees: high quality service is given by concierges and teachers beyond direct financial incentives to do so. Even if these same teachers and concierges are trying to get increased wages, the services they provide are free of these considerations. Salary negotiations are a matter between employers and employees. Those who receive services are customers of the employers, not the employees. There’d be no reason for a concierge or teacher to argue with customers and students about their salaries.

In a way, this is almost the opposite of “social alienation”. In social sciences. “alienation” refers to a feeling of estrangement often taking place among workers whose products are consumed by people with whom they have no connection. A worker at a Foxconn factory may feel alienated from the person who will buy the Dell laptop on which she’s working. But service work is quite distinct from this. While there may be a huge status differential between someone getting a service and the person providing it and there can be a feeling of distance, the fact that there’s a direct connection between the two is quite significant. Even someone working at a call centre in India providing technical support to a high-status customer in the US is significantly different from the alienated factory worker. The direct connection between call centre employee and customer can have a significant impact on both people involved, and on the business behind the technical support request.

And, to a large extent, the further a person working in customer service is from the financial transaction, the higher the quality of the service.

Lots has been said about Zappos and about Nordstrom. Much of that has to do with how these two companies’ approaches to customer service differ from other approaches (for instance, avoiding scripts). But there might be a key lesson, here, in terms of distancing the service from the job. The “customers are always right” ethos doesn’t jive well with beancounting.

So, concierge-style service is “more than a job”.

Providing high-quality service can be highly stimulating, motivating, and satisfying. Haven’t looked at job satisfaction levels among these people, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they were quite high. What managers seem to forget, about job satisfaction, is that it has an impact beyond employee retention, productivity, and reputation. Satisfying jobs have a broad impact on society, which then impacts business. Like Ford paying high wages for his workers, much of it has to do with having a broader vision than simply managing the “ins and outs” of a given business. This is where Hanifan’s concept of social capital may come into play. Communities are built through such things as trust and job satisfaction.

Again, these aren’t simple issues. Quality customer service isn’t a simple matter of giving people the right conditions. But its effect are far-reaching.

It’s interesting to hear about “corporate concierge services” offered to employees of certain businesses. In a way, they loop back the relationship between high-quality service and labour. It sounds like corporate concierges can do a lot to enhance a workplace, even making it more sustainable. I’d be curious to know more about them, as it sounds like they might have an interesting position with regards to the enterprise. I wouldn’t be surprised if their status were separate from that of regular employees within the business.

And, of course, I wish I were working at a place where such services were available. Sounds like those workplaces aren’t that uncommon. But having access to such services would be quite a privilege.

Thing is, I hate privilege, even when I’m the one benefitting from it. I once quipped that I hated library privileges, because they’re unequally distributed. The core of this is that I wish society were more equal. Not by levelling down everything we have, but by providing broader access to resources and services.

A key problem with concierge-style services is that access to them tends to be restricted. But it doesn’t sound like their costs are the only factor for this exclusiveness. In a way, concierge-level service may not be that much more expensive than standard service. It might be about concierge-style services being a differentiating factor, but even that doesn’t imply that it should be so restricted.

I’d argue that the level of quality of service that I’ve been describing (and rambling on about) can be found in just about any context. I’ve observed the work of librarians, gas station attendants, police officers, street vendors, park rangers, and movers who provided this level of service. While it may difficult to sustain high-quality service, it does scale and it does seem to make life easier for everyone.

Open Letter: UnivCafé Testimonial

Here’s a slightly edited version of a message I sent about University of the Streets Café. I realize that my comments about it may sound strange for people who haven’t participated in one of their conversations. And there may be people who don’t like it as much as I do. But it’s remarkable how favourable people are to the program, once they participate in it.

Having taught at eight academic institutions in the United States and Canada, I have frequently gone on record to say that Concordia is my favourite context for teaching and learning. By a long stretch.

Concordia’s “University of the Streets Café” program is among the things I like the most about my favourite university.

Over the past few years, I have been a vocal participant at a rather large number of “UnivCafé” events and have been the guest at one of them. Each of these two-hour conversations has provided me with more stimulation than any seminar or class meeting in which I participated, as a teacher or as a student.

In fact, I have frequently discussed UnivCafé with diverse people (including several members of the Concordia community). As is clear to anyone who knows me, UnivCafé has had a strong impact on my life, both professionally and personally.

Given my experience elsewhere, I have a clear impression of what makes Concordia unique.

- Emphasis on community development.

- Strong social awareness.

- Thoughtful approach to sustainability.

- Seamless English/French bilingualism.

- Inclusive attitude, embracing cultural and social diversity.

- Ease of building organic social networks through informal events.

In a way, UnivCafé encapsulates Concordia’s uniqueness.

Yet it goes further than that. Though it may sound hyperbolic to outsiders, I would not hesitate to say that UnivCafé captures some of the Greek academia (Ἀκαδημία) while integrating dimensions of contemporary life. More pithily: ”UnivCafé is a social media version of Plato‘s Academy”.

It seems to me that academia is in a transition period. For instance, the tenure system could be rethought. With social and technological developments challenging many academic models, universities are often searching for new models. I sincerely hope that the UnivCafé model is a sign of things to come.

I have discussed this on several occasions with students and colleagues, and this notion is gaining ground.

There is something remarkable about how appropriate the UnivCafé model is, in the current context. To my mind, UnivCafé does all of the following:

- Encourages critical thinking.

- Gives voice to people who are rarely heard.

- Exposes participants to a diversity of perspectives.

- Brings together people who rarely get a chance to interact.

- Integrates practical and theoretical concerns.

- Allays fears of public speaking.

- Builds valuable connections through the local community.

- Brings academics outside the Ivory Tower.

As may be obvious, I could talk about UnivCafé for hours and would be happy to do so in any context.

In the meantime, may this testimonial serve as a token of appreciation for all the things I have gained from UnivCafé.

Intimacy, Network Effect, Hype

Is “intimacy” a mere correlate of the network effect?

Can we use the network effect to explain what has been happening with Quora?

Is the Quora hype related to network effect?

I really don’t feel a need to justify my dislike of Quora. Oh, sure, I can explain it. At length. Even on Quora itself. And elsewhere. But I tend to sense some defensiveness on the part of Quora fans.

[Speaking of fans, I have blogposts on fanboism laying in my head, waiting to be hatched. Maybe this will be part of it.]

But the important point, to me, isn’t about whether or not I like Quora. It’s about what makes Quora so divisive. There are people who dislike it and there are some who defend it.

Originally, I was only hearing from contacts and friends who just looooved Quora. So I was having a “Ionesco moment”: why is it that seemingly “everyone” who uses it loves Quora when, to me, it represents such a move in the wrong direction? Is there something huge I’m missing? Or has that world gone crazy?

It was a surreal experience.

And while I’m all for surrealism, I get this strange feeling when I’m so unable to understand a situation. It’s partly a motivation for delving into the issue (I’m surely not the only ethnographer to get this). But it’s also unsettling.

And, for Quora at least, this phase seems to be over. I now think I have a good idea as to what makes for such a difference in people’s experiences with Quora.

It has to do with the network effect.

I’m sure some Quora fanbois will disagree, but it’s now such a clear picture in my mind that it gets me into the next phase. Which has little to do with Quora itself.

The “network effect” is the kind of notion which is so commonplace that few people bother explaining it outside of introductory courses (same thing with “group forming” in social psychology and sociology, or preferential marriage patterns in cultural anthropology). What someone might call (perhaps dismissively): “textbook stuff.”

I’m completely convinced that there’s a huge amount of research on the network effect, but I’m also guessing few people looking it up. And I’m accusing people, here. Ever since I first heard of it (in 1993, or so), I’ve rarely looked at explanations of it and I actually don’t care about the textbook version of the concept. And I won’t “look it up.” I’m more interested in diverse usage patterns related to the concept (I’m a linguistic anthropologist).

So, the version I first heard (at a time when the Internet was off most people’s radar) was something like: “in networked technology, you need critical mass for the tools to become truly useful. For instance, the telephone has no use if you’re the only one with one and it has only very limited use if you can only call a single person.” Simple to the point of being simplistic, but a useful reminder.

Over the years, I’ve heard and read diverse versions of that same concept, usually in more sophisticated form, but usually revolving around the same basic idea that there’s a positive effect associated with broader usage of some networked technology.

I’m sure specialists have explored every single implication of this core idea, but I’m not situating myself as a specialist of technological networks. I’m into social networks, which may or may not be associated with technology (however defined). There are social equivalents of the “network effect” and I know some people are passionate about those. But I find that it’s quite limiting to focus so exclusively on quantitative aspects of social networks. What’s so special about networks, in a social science perspective, isn’t scale. Social scientists are used to working with social groups at any scale and we’re quite aware of what might happen at different scales. But networks are fascinating because of different features they may have. We may gain a lot when we think of social networks as acephalous, boundless, fluid, nameless, indexical, and impactful. [I was actually lecturing about some of this in my “Intro to soci” course, yesterday…]

So, from my perspective, “network effect” is an interesting concept when talking about networked technology, in part because it relates to the social part of those networks (innovation happens mainly through technological adoption, not through mere “invention”). But it’s not really the kind of notion I’d visit regularly.

This case is somewhat different. I’m perceiving something rather obvious (and which is probably discussed extensively in research fields which have to do with networked technology) but which strikes me as missing from some discussions of social networking systems online. In a way, it’s so obvious that it’s kind of difficult to explain.

But what’s coming up in my mind has to do with a specific notion of “intimacy.” It’s actually something which has been on my mind for a while and it might still need to “bake” a bit longer before it can be shared properly. But, like other University of the Streets participants, I perceive the importance of sharing “half-baked thoughts.”

And, right now, I’m thinking of an anecdotal context which may get the point across.

Given my attendance policy, there are class meetings during which a rather large proportion of the class is missing. I tend to call this an “intimate setting,” though I’m aware that it may have different connotations to different people. From what I can observe, people in class get the point. The classroom setting is indeed changing significantly and it has to do with being more “intimate.”

Not that we’re necessarily closer to one another physically or intellectually. It needs not be a “bonding experience” for the situation to be interesting. And it doesn’t have much to do with “absolute numbers” (a classroom with 60 people is relatively intimate when the usual attendance is close to 100; a classroom with 30 people feels almost overwhelming when only 10 people were showing up previously). But there’s some interesting phenomenon going on when there are fewer people than usual, in a classroom.

Part of this phenomenon may relate to motivation. In some ways, one might expect that those who are attending at that point are the “most dedicated students” in the class. This might be a fairly reasonable assumption in the context of a snowstorm but it might not work so well in other contexts (say, when the incentive to “come to class” relates to extrinsic motivation). So, what’s interesting about the “intimate setting” isn’t necessarily that it brings together “better people.” It’s that something special goes on.

What’s going on, with the “intimate classroom,” can vary quite a bit. But there’s still “something special” about it. Even when it’s not a bonding experience, it’s still a shared experience. While “communities of practice” are fascinating, this is where I tend to care more about “communities of experience.” And, again, it doesn’t have much to do with scale and it may have relatively little to do with proximity (physical or intellectual). But it does have to do with cognition and communication. What is special with the “intimate classroom” has to do with shared assumptions.

Going back to Quora…

While an online service with any kind of network effect is still relatively new, there’s something related to the “intimate setting” going on. In other words, it seems like the initial phase of the network effect is the “intimacy” phase: the service has a “large enough userbase” to be useful (so, it’s achieved a first type of critical mass) but it’s still not so “large” as to be overwhelming.

During that phase, the service may feel to people like a very welcoming place. Everyone can be on a “first-name basis. ” High-status users mingle with others as if there weren’t any hierarchy. In this sense, it’s a bit like the liminal phase of a rite of passage, during which communitas is achieved.

This phase is a bit like the Golden Age for an online service with a significant “social dimension.” It’s the kind of time which may make people “wax nostalgic about the good ole days,” once it’s over. It’s the time before the BYT comes around.

Sure, there’s a network effect at stake. You don’t achieve much of a “sense of belonging” by yourself. But, yet again, it’s not really a question of scale. You can feel a strong bond in a dyad and a team of three people can perform quite well. On the other hand, the cases about which I’m thinking are orders of magnitude beyond the so-called “Dunbar number” which seems to obsess so many people (outside of anthro, at least).

Here’s where it might get somewhat controversial (though similar things have been said about Quora): I’d argue that part of this “intimacy effect” has to do with a sense of “exclusivity.” I don’t mean this as the way people talk about “elitism” (though, again, there does seem to be explicit elitism involved in Quora’s case). It’s more about being part of a “select group of people.” About “being there at the time.” It can get very elitist, snobbish, and self-serving very fast. But it’s still about shared experiences and, more specifically, about the perceived boundedness of communities of experience.

We all know about early adopters, of course. And, as part of my interest in geek culture, I keep advocating for more social awareness in any approach to the adoption part of social media tools. But what I mean here isn’t about a “personality type” or about the “attributes of individual actors.” In fact, this is exactly a point at which the study of social networks starts deviating from traditional approaches to sociology. It’s about the special type of social group the “initial userbase” of such a service may represent.

From a broad perspective (as outsiders, say, or using the comparativist’s “etic perspective”), that userbase is likely to be rather homogeneous. Depending on the enrollment procedure for the service, the structure of the group may be a skewed version of an existing network structure. In other words, it’s quite likely that, during that phase, most of the people involved were already connected through other means. In Quora’s case, given the service’s pushy overeagerness on using Twitter and Facebook for recruitment, it sounds quite likely that many of the people who joined Quora could already be tied through either Twitter or Facebook.

Anecdotally, it’s certainly been my experience that the overwhelming majority of people who “follow me on Quora” have been part of my first degree on some social media tool in the recent past. In fact, one of my main reactions as I’ve been getting those notifications of Quora followers was: “here are people with whom I’ve been connected but with whom I haven’t had significant relationships.” In some cases, I was actually surprised that these people would “follow” me while it appeared like they actually weren’t interested in having any kind of meaningful interactions. To put it bluntly, it sometimes appeared as if people who had been “snubbing” me were suddenly interested in something about me. But that was just in the case of a few people I had unsuccessfully tried to engage in meaningful interactions and had given up thinking that we might not be that compatible as interlocutors. Overall, I was mostly surprised at seeing the quick uptake in my follower list, which doesn’t tend to correlate with meaningful interaction, in my experience.

Now that I understand more about the unthinking way new Quora users are adding people to their networks, my surprise has transformed into an additional annoyance with the service. In a way, it’s a repeat of the time (what was it? 2007?) when Facebook applications got their big push and we kept receiving those “app invites” because some “social media mar-ke-tors” had thought it wise to force people to “invite five friends to use the service.” To Facebook’s credit (more on this later, I hope), these pushy and thoughtless “invitations” are a thing of the past…on those services where people learnt a few lessons about social networks.

Perhaps interestingly, I’ve had a very similar experience with Scribd, at about the same time. I was receiving what seemed like a steady flow of notifications about people from my first degree online network connecting with me on Scribd, whether or not they had ever engaged in a meaningful interaction with me. As with Quora, my initial surprise quickly morphed into annoyance. I wasn’t using any service much and these meaningless connections made it much less likely that I would ever use these services to get in touch with new and interesting people. If most of the people who are connecting with me on Quora and Scribd are already in my first degree and if they tend to be people I have limited interactions, why would I use these services to expand the range of people with whom I want to have meaningful interactions? They’re already within range and they haven’t been very communicative (for whatever reason, I don’t actually assume they were consciously snubbing me). Investing in Quora for “networking purposes” seemed like a futile effort, for me.

Perhaps because I have a specific approach to “networking.”

In my networking activities, I don’t focus on either “quantity” or “quality” of the people involved. I seriously, genuinely, honestly find something worthwhile in anyone with whom I can eventually connect, so the “quality of the individuals” argument doesn’t work with me. And I’m seriously, genuinely, honestly not trying to sell myself on a large market, so the “quantity” issue is one which has almost no effect on me. Besides, I already have what I consider to be an amazing social network online, in terms of quality of interactions. Sure, people with whom I interact are simply amazing. Sure, the size of my first degree network on some services is “well above average.” But these things wouldn’t matter at all if I weren’t able to have meaningful interactions in these contexts. And, as it turns out, I’m lucky enough to be able to have very meaningful interactions in a large range of contexts, both offline and on. Part of it has to do with the fact that I’m teaching addict. Part of it has to do with the fact that I’m a papillon social (social butterfly). It may even have to do with a stage in my life, at which I still care about meeting new people but I don’t really need new people in my circle. Part of it makes me much less selective than most other people (I like to have new acquaintances) and part of it makes me more selective (I don’t need new “friends”). If it didn’t sound condescending, I’d say it has to do with maturity. But it’s not about my own maturity as a human being. It’s about the maturity of my first-degree network.

There are other people who are in an expansionist phase. For whatever reason (marketing and job searches are the best-known ones, but they’re really not the only ones), some people need to get more contacts and/or contacts with people who have some specific characteristics. For instance, there are social activists out there who need to connect to key decision-makers because they have a strong message to carry. And there are people who were isolated from most other people around them because of stigmatization who just need to meet non-judgmental people. These, to me, are fine goals for someone to expand her or his first-degree network.

Some of it may have to do with introversion. While extraversion is a “dominant trait” of mine, I care deeply about people who consider themselves introverts, even when they start using it as a divisive label. In fact, that’s part of the reason I think it’d be neat to hold a ShyCamp. There’s a whole lot of room for human connection without having to rely on devices of outgoingness.

So, there are people who may benefit from expansion of their first-degree network. In this context, the “network effect” matters in a specific way. And if I think about “network maturity” in this case, there’s no evaluation involved, contrary to what it may seem like.

As you may have noticed, I keep insisting on the fact that we’re talking about “first-degree network.” Part of the reason is that I was lecturing about a few key network concepts just yesterday so, getting people to understand the difference between “the network as a whole” (especially on an online service) and “a given person’s first-degree network” is important to me. But another part relates back to what I’m getting to realize about Quora and Scribd: the process of connecting through an online service may have as much to do with collapsing some degrees of separation than with “being part of the same network.” To use Granovetter’s well-known terms, it’s about transforming “weak ties” into “strong” ones.

And I specifically don’t mean it as a “quality of interaction.” What is at stake, on Quora and Scribd, seems to have little to do with creating stronger bonds. But they may want to create closer links, in terms of network topography. In a way, it’s a bit like getting introduced on LinkedIn (and it corresponds to what biz-minded people mean by “networking”): you care about having “access” to that person, but you don’t necessarily care about her or him, personally.

There’s some sense in using such an approach on “utilitarian networks” like professional or Q&A ones (LinkedIn does both). But there are diverse ways to implement this approach and, to me, Quora and Scribd do it in a way which is very precisely counterproductive. The way LinkedIn does it is context-appropriate. So is the way Academia.edu does it. In both of these cases, the “transaction cost” of connecting with someone is commensurate with the degree of interaction which is possible. On Scribd and Quora, they almost force you to connect with “people you already know” and the “degree of interaction” which is imposed on users is disproportionately high (especially in Quora’s case, where a contact of yours can annoy you by asking you personally to answer a specific question). In this sense, joining Quora is a bit closer to being conscripted in a war while registering on Academia.edu is just a tiny bit more like getting into a country club. The analogies are tenuous but they probably get the point across. Especially since I get the strong impression that the “intimacy phase” has a lot to do with the “country club mentality.”

See, the social context in which these services gain much traction (relatively tech-savvy Anglophones in North America and Europe) assign very negative connotations to social exclusion but people keep being fascinating by the affordances of “select clubs” in terms of social capital. In other words, people may be very vocal as to how nasty it would be if some people had exclusive access to some influential people yet there’s what I perceive as an obsession with influence among the same people. As a caricature: “The ‘human rights’ movement leveled the playing field and we should never ever go back to those dark days of Old Boys’ Clubs and Secret Societies. As soon as I become the most influential person on the planet, I’ll make sure that people who think like me get the benefits they deserve.”

This is where the notion of elitism, as applied specifically to Quora but possibly expanding to other services, makes the most sense. “Oh, no, Quora is meant for everyone. It’s Democratic! See? I can connect with very influential people. But, isn’t it sad that these plebeians are coming to Quora without a proper knowledge of the only right way to ask questions and without proper introduction by people I can trust? I hate these n00bz! Even worse, there are people now on the service who are trying to get social capital by promoting themselves. The nerve on these people, to invade my own dedicated private sphere where I was able to connect with the ‘movers and shakers’ of the industry.” No wonder Quora is so journalistic.

But I’d argue that there’s a part of this which is a confusion between first-degree networks and connection. Before Quora, the same people were indeed connected to these “influential people,” who allegedly make Quora such a unique system. After all, they were already online and I’m quite sure that most of them weren’t more than three or four degrees of separation from Quora’s initial userbase. But access to these people was difficult because connections were indirect. “Mr. Y Z, the CEO of Company X was already in my network, since there were employees of Company X who were connected through Twitter to people who follow me. But I couldn’t just coldcall CEO Z to ask him a question, since CEOs are out of reach, in their caves. Quora changed everything because Y responded to a question by someone ‘totally unconnected to him’ so it’s clear, now, that I have direct access to my good ol’ friend Y’s inner thoughts and doubts.”

As RMS might say, this type of connection is a “seductive mirage.” Because, I would argue, not much has changed in terms of access and whatever did change was already happening all over this social context.

At the risk of sounding dismissive, again, I’d say that part of what people find so alluring in Quora is “simply” an epiphany about the Small World phenomenon. With all sorts of fallacies caught in there. Another caricature: “What? It takes only three contacts for me to send something from rural Idaho to the head honcho at some Silicon Valley firm? This is the first time something like this happens, in the History of the Whole Wide World!”

Actually, I do feel quite bad about these caricatures. Some of those who are so passionate about Quora, among my contacts, have been very aware of many things happening online since the early 1990s. But I have to be honest in how I receive some comments about Quora and much of it sounds like a sudden realization of something which I thought was a given.

The fact that I feel so bad about these characterizations relates to the fact that, contrary to what I had planned to do, I’m not linking to specific comments about Quora. Not that I don’t want people to read about this but I don’t want anyone to feel targeted. I respect everyone and my characterizations aren’t judgmental. They’re impressionistic and, again, caricatures.

Speaking of what I had planned, beginning this post… I actually wanted to talk less about Quora specifically and more about other issues. Sounds like I’m currently getting sidetracked, and it’s kind of sad. But it’s ok. The show must go on.

So, other services…

While I had a similar experiences with Scribd and Quora about getting notifications of new connections from people with whom I haven’t had meaningful interactions, I’ve had a very different experience on many (probably most) other services.

An example I like is Foursquare. “Friendship requests” I get on Foursquare are mostly from: people with whom I’ve had relatively significant interactions in the past, people who were already significant parts of my second-degree network, or people I had never heard of. Sure, there are some people with whom I had tried to establish connections, including some who seem to reluctantly follow me on Quora. But the proportion of these is rather minimal and, for me, the stakes in accepting a friend request on Foursquare are quite low since it’s mostly about sharing data I already share publicly. Instead of being able to solicit my response to a specific question, the main thing my Foursquare “friends” can do that others can’t is give me recommendations, tips, and “notifications of their presence.” These are all things I might actually enjoy, so there’s nothing annoying about it. Sure, like any online service with a network component, these days, there are some “friend requests” which are more about self-promotion. But those are usually easy to avoid and, even if I get fooled by a “social media mar-ke-tor,” the most this person may do to me is give usrecommendation about “some random place.” Again, easy to avoid. So, the “social network” dimension of Foursquare seems appropriate, to me. Not ideal, but pretty decent.

I never really liked the “game” aspect and while I did play around with getting badges and mayorships in my first few weeks, it never felt like the point of Foursquare, to me. As Foursquare eventually became mainstream in Montreal and I was asked by a journalist about my approach to Foursquare, I was exactly in the phase when I was least interested in the game aspect and wished we could talk a whole lot more about the other dimensions of the phenomenon.

And I realize that, as I’m saying this, I may sound to some as exactly those who are bemoaning the shift out of the initial userbase of some cherished service. But there are significant differences. Note that I’m not complaining about the transition in the userbase. In the Foursquare context, “the more the merrier.” I was actually glad that Foursquare was becoming mainstream as it was easier to explain to people, it became more connected with things business owners might do, and generally had more impact. What gave me pause, at the time, is the journalistic hype surrounding Foursquare which seemed to be missing some key points about social networks online. Besides, I was never annoyed by this hype or by Foursquare itself. I simply thought that it was sad that the focus would be on a dimension of the service which was already present on not only Dodgeball and other location-based services but, pretty much, all over the place. I was critical of the seemingly unthinking way people approached Foursquare but the service itself was never that big a deal for me, either way.

And I pretty much have the same attitude toward any tool. I happen to have my favourites, which either tend to fit neatly in my “workflow” or otherwise have some neat feature I enjoy. But I’m very wary of hype and backlash. Especially now. It gets old very fast and it’s been going for quite a while.

Maybe I should just move away from the “tech world.” It’s the context for such hype and buzz machine that it almost makes me angry. [I very rarely get angry.] Why do I care so much? You can say it’s accumulation, over the years. Because I still care about social media and I really do want to know what people are saying about social media tools. I just wish discussion of these tools weren’t soooo “superlative”…

Obviously, I digress. But this is what I like to do on my blog and it has a cathartic effect. I actually do feel better now, thank you.

And I can talk about some other things I wanted to mention. I won’t spend much time on them because this is long enough (both as a blogpost and as a blogging session). But I want to set a few placeholders, for further discussion.

One such placeholder is about some pet theories I have about what worked well with certain services. Which is exactly the kind of thing “social media entrepreneurs” and journalists are so interested in, but end up talking about the same dimensions.

Let’s take Twitter, for instance. Sure, sure, there’s been a lot of talk about what made Twitter a success and probably-everybody knows that it got started as a side-project at Odeo, and blah, blah, blah. Many people also realize that there were other microblogging services around as Twitter got traction. And I’m sure some people use Twitter as a “textbook case” of “network effect” (however they define that effect). I even mention the celebrity dimensions of the “Twitter phenomenon” in class (my students aren’t easily starstruck by Bieber and Gaga) and I understand why journalists are so taken by Twitter’s “broadcast” mission. But something which has been discussed relatively rarely is the level of responsiveness by Twitter developers, over the years, to people’s actual use of the service. Again, we all know that “@-replies,” “hashtags,” and “retweets” were all emerging usage patterns that Twitter eventually integrated. And some discussion has taken place when Twitter changed it’s core prompt to reflect the fact that the way people were using it had changed. But there’s relatively little discussion as to what this process implies in terms of “developing philosophy.” As people are still talking about being “proactive” (ugh!) with users, and crude measurements of popularity keep being sold and bandied about, a large part of the tremendous potential for responsiveness (through social media or otherwise) is left untapped. People prefer to hype a new service which is “likely to have Twitter-like success because it has the features users have said they wanted in the survey we sell.” Instead of talking about the “get satisfaction” effect in responsiveness. Not that “consumers” now have “more power than ever before.” But responsive developers who refrain from imposing their views (Quora, again) tend to have a more positive impact, socially, than those which are merely trying to expand their userbase.

Which leads me to talk about Facebook. I could talk for hours on end about Facebook, but I almost feel afraid to do so. At this point, Facebook is conceived in what I perceive to be such a narrow way that it seems like anything I might say would sound exceedingly strange. Given the fact that it was part one of the first waves of Web tools with explicit social components to reach mainstream adoption, it almost sounds “historical” in timeframe. But, as so many people keep saying, it’s just not that old. IMHO, part of the implication of Facebook’s relatively young age should be that we are able to discuss it as a dynamic process, instead of assigning it to a bygone era. But, whatever…

Actually, I think part of the reason there’s such lack of depth in discussing Facebook is also part of the reason it was so special: it was originally a very select service. Since, for a significant period of time, the service was only available to people with email addresses ending in “.edu,” it’s not really surprising that many of the people who keep discussing it were actually not on the service “in its formative years.” But, I would argue, the fact that it was so exclusive at first (something which is often repeated but which seems to be understood in a very theoretical sense) contributed quite significantly to its success. Of course, similar claims have been made but, I’d say that my own claim is deeper than others.

[Bang! I really don’t tend to make claims so, much of this blogpost sounds to me as if it were coming from somebody else…]

Ok, I don’t mean it so strongly. But there’s something I think neat about the Facebook of 2005, the one I joined. So I’d like to discuss it. Hence the placeholder.

And, in this placeholder, I’d fit: the ideas about responsiveness mentioned with Twitter, the stepwise approach adopted by Facebook (which, to me, was the real key to its eventual success), the notion of intimacy which is the true core of this blogpost, the notion of hype/counterhype linked to journalistic approaches, a key distinction between privacy and intimacy, some non-ranting (but still rambling) discussion as to what Google is missing in its “social” projects, anecdotes about “sequential network effects” on Facebook as the service reached new “populations,” some personal comments about what I get out of Facebook even though I almost never spent any significant amount of time on it, some musings as to the possibility that there are online services which have reached maturity and may remain stable in the foreseeable future, a few digressions about fanboism or about the lack of sophistication in the social network models used in online services, and maybe a bit of fun at the expense of “social media expert marketors”…

But that’ll be for another time.

Cheers!

I Hate Books

In a way, this is a followup to a discussion happening on Facebook after something I posted (available publicly on Twitter): “(Alexandre) wishes physical books a quick and painfree death. / aime la connaissance.”

As I expected, the reactions I received were from friends who are aghast: how dare I dismiss physical books? Don’t I know no shame?

Apparently, no, not in this case.

And while I posted it as a quip, it’s the result of a rather long reflection. It’s not that I’m suddenly anti-books. It’s that I stopped buying several of the “pro-book” arguments a while ago.

Sure, sure. Books are the textbook case of technlogy which needs no improvement. eBooks can’t replace the experience of doing this or that with a book. But that’s what folkloristics defines as a functional shift. Like woven baskets which became objects of nostalgia, books are being maintained as the model for a very specific attitude toward knowledge construction based on monolithic authored texts vetted by gatekeepers and sold as access to information.

An important point, here, is that I’m not really thinking about fiction. I used to read two novel-length works a week (collections of short stories, plays…), for a period of about 10 years (ages 13 to 23). So, during that period, I probably read about 1,000 novels, ranging from Proust’s Recherche to Baricco’s Novecentoand the five books of Rabelais’s Pantagruel series. This was after having read a fair deal of adolescent and young adult fiction. By today’s standards, I might be considered fairly well-read.

My life has changed a lot, since that time. I didn’t exactly stop reading fiction but my move through graduate school eventually shifted my reading time from fiction to academic texts. And I started writing more and more, online and offline.

In the same time, the Web had also been making me shift from pointed longform texts to copious amounts of shortform text. Much more polyvocal than what Bakhtin himself would have imagined.

(I’ve also been shifting from French to English, during that time. But that’s almost another story. Or it’s another part of the story which can reamin in the backdrop without being addressed directly at this point. Ask, if you’re curious.)

The increase in my writing activity is, itself, a shift in the way I think, act, talk… and get feedback. See, the fact that I talk and write a lot, in a variety of circumstances, also means that I get a lot of people to play along. There’s still a risk of groupthink, in specific contexts, but one couldn’t say I keep getting things from the same perspective. In fact, the very Facebook conversation which sparked this blogpost is an example, as the people responding there come from relatively distant backgrounds (though there are similarities) and were not specifically queried about this. Their reactions have a very specific value, to me. Sure, it comes in the form of writing. But it’s giving me even more of something I used to find in writing: insight. The stuff you can’t get through Google.

So, back to books.

I dislike physical books. I wish I didn’t have to use them to read what I want to read. I do have a much easier time with short reading sessions on a computer screen that what would turn into rather long periods of time holding a book in my hands.

Physical books just don’t do it for me, anymore. The printing press is, like, soooo 1454!

Yes, books had “a good run.” No, nothing replaces them. That’s not the way it works. Movies didn’t replace theater, television didn’t replace radio, automobiles didn’t replace horses, photographs didn’t replace paintings, books didn’t replace orality. In fact, the technology itself doesn’t do much by itself. But social contexts recontextualize tools. If we take technology to be the set of both tools and the knowledge surrounding it, technology mostly goes through social processes, since tool repertoires and corresponding knowledge mostly shift in social contexts, not in their mere existence. Gutenberg’s Bible was a “game-changer” for social, as well as technical reasons.

And I do insist on orality. Journalists and other “communication is transmission of information” followers of Shannon&Weaver tend to portray writing as the annihilation of orality. How long after the invention of writing did Homer transfer an oral tradition to the writing media? Didn’t Albert Lord show the vitality of the epic well into the 20th Century? Isn’t a lot of our knowledge constructed through oral means? Is Internet writing that far, conceptually, from orality? Is literacy a simple on/off switch?

Not only did I maintain an interest in orality through the most book-focused moments of my life but I probably care more about orality now than I ever did. So I simply cannot accept the idea that books have simply replaced the human voice. It doesn’t add up.

My guess is that books won’t simply disappear either. There should still be a use for “coffee table books” and books as gifts or collectables. Records haven’t disappeared completely and CDs still have a few more days in dedicated stores. But, in general, we’re moving away from the “support medium” for “content” and more toward actual knowledge management in socially significant contexts.

In these contexts, books often make little sense. Reading books is passive while these contexts are about (hyper-)/(inter-)active.

Case in point (and the reason I felt compelled to post that Facebook/Twitter quip)…

I hear about a “just released” French book during a Swiss podcast. Of course, it’s taken a while to write and publish. So, by the time I heard about it, there was no way to participate in the construction of knowledge which led to it. It was already “set in stone” as an “opus.”

Looked for it at diverse bookstores. One bookstore could eventually order it. It’d take weeks and be quite costly (for something I’m mostly curious about, not depending on for something really important).